The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 27

Episode 27: I called the police’s Dahmer witnesses out of the blue. They’d been waiting for my call -- or anybody's call.

Link to Episode 26: Where Dahmer worked on the beach in Sunny Isles: A pizza shop — which meant deliveries — store vehicles — which were easily taken by employees for their own use. A blue van.

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Next I looked for the two witnesses who in 1991 had told Hollywood Police they’d seen Dahmer at the mall. Willis Morgan was in the phone book at the same number he’d given police in 1991.

Although 11 years had passed since his statement, 21 from after the event and 6 since the case file was made public, it was like he’d been waiting all that time for someone like me to call. No one had.

“I know the person I saw was the person who took Adam Walsh,” he gushed right off the bat. Was he still certain that the person he saw was Dahmer? Yes, absolutely. But then he hedged, because the man he’d seen had long hair, to his collar, and Jack Hoffman had told him that Dahmer didn’t have long hair because he’d recently been released from the military.

From the end of March, when Dahmer had been discharged, to the end of July, when Adam went missing, it had been four months.

But Morgan still thought that’s who he saw.

I asked him to describe what happened. He was in Hollywood Mall at Radio Shack, browsing the Red Tag sale table in the middle of the front of the store. The mall was dead, he remembered, at least around there. Radio Shack was the second store inside the mall’s north entrance, and in his side vision he saw a man come in through the mall’s glass doors and stop near the Radio Shack entrance, about 12 feet from him.

They made eye contact. Then the man smiled and said, “Hi there, nice day, isn’t it?”

“He was a nutcase. He wanted to talk to somebody. I didn’t want to look at him. He stood and stared me down hard, for an eternity. If you asked me how long, I’d say probably 20 seconds, but it felt like 10 minutes.”

When the man became angry, Morgan looked away, thinking he might leave. Instead, the man entered the store and approached him at arm’s length. As if he was starting over again, he smiled and repeated – at the same volume and cadence as before, “Hi there, nice day, isn’t it?”

Again Morgan didn’t respond. “I was thinking, why is he talking so loud? He’s standing right next to me. He must want someone to talk to, really badly.” Morgan pretended to be interested in the store item he’d already picked up, but he was keeping a peripheral eye on the man’s hands. The man looked as if he was ready to fight or assault him.

“A sense came over me – I thought he wanted to pull my arm and pull me out of the store. I thought, did he have a knife?” Just in case, Morgan used his left arm to cover his rib cage.

Morgan had a prosthetic leg, the result of a motorcycle accident, so he couldn’t easily dart away from the man, nor did he want him to see his limp. He looked over his shoulder for a witness or someone to help, but the only other person in the store was in the back, stocking shelves. Then abruptly, the man about-faced and stormed out, apparently feeling rebuffed and angry.

Morgan described him as similar to his own size – 5’10 or 5’11, 180 pounds. He wore blue jeans, but “everything about him was disheveled. He’d been drinking. He was totally unkempt.”

What he remembered most about him was his eyes: “He had a look on him, like the devil was in him.” When he’d stared at him, “I felt like he was trying to look at the back of my skull.”

When the man left, Morgan decided he needed to follow him because he thought he’d approach someone else, who might need help. He also decided he needed to commit his face to memory. “That’s how scary this was.”

As the man walked the mall, Morgan kept a safe distance directly in back of him, figuring he was less likely to turn 180 degrees than, say, 135 degrees, to one side. The man didn’t seem to realize he was being trailed. The man entered Sears, and then its toy department. Sears was also mostly empty of customers, he said. Inside the store, to hide, Morgan walked between clothes racks in the men’s department. But the toy department was at the back end of the store, so he figured that the man would have to reverse his path. That’s when Morgan decided to leave.

Passing the perfume counter and the two young women behind it he thought about asking them to call security, but instead he hurried out of the store. He saw no kids in the toy department. Only after he got into his car and locked the door did he feel safe.

Morgan didn’t think to note the exact time when he’d been in the mall, but thought it was sometime midday. In 1981, as in 1991, he worked at The Miami Herald in the press room at night, Wednesday to Saturday, until dawn the next day. He said he usually slept until noon, but on Sunday nights he tended to fall asleep just after midnight and awaken in the late morning Monday.

He recalled that he went to the mall first thing that Monday. He’d planned to eat lunch at the German deli, but first he browsed travel books for about 20 minutes at Waldenbooks. It was a week or two before he went to Mexico, he remembered. Then he went into Radio Shack. He ended up eating lunch away from the mall, at Denny’s.

That night, on local TV news he saw that a family was looking for their child who’d been lost in Sears’s toy department. He was floored; he was sure it must have been because of the man he’d followed. He told a neighbor the next morning, Tuesday, and when he returned to work Wednesday evening, his buddies there urged him to report it to Hollywood Police.

Rather than go to sleep at his normal time, just after sunrise, he stayed up and got to the police station around nine Thursday morning. In the lobby was an officer specially assigned to receive tips. Trying to recall his name for me, he thought out loud and said Officer Elvis – then said Officer Presley. He wrote down Morgan’s name, address and information but wasn’t much interested. He asked if he’d seen the man leave in a vehicle. He said that his encounter had been inside the mall.

Did you get his license plate? the officer asked.

No, he said, I didn’t see him outside.

The police never called back, he said.

I hadn’t found any reference to Morgan in the file before 1991, but Hoffman had since said that a lot of early tips were lost.

Since his job was to prepare the presses, Morgan said that part of his work was to read the newspaper’s pages, front to back. Besides, the job had a lot of down time and he had nothing else to do. In 1983, he remembered, a printing clerk showed him a front-page photo of Ottis Toole, destined for the press. She asked, “Willis, is this the guy?”

No, he said. But in 1991, he saw a photo he did recognize.

“I was freaking out. This is the guy! This was the guy I followed in the mall! My supervisor had to calm me down.”

The photo was of Jeffrey Dahmer.

When Jack Hoffman finally took his story, he’d shared none of Morgan’s excitement. Later Hoffman told him, “It couldn’t be Dahmer. Dahmer’s been dismissed as a suspect.”

“He so totally, completely discounted Dahmer. He kept convincing me it wasn’t Dahmer.”

Morgan then took his story elsewhere. He wrote to John Walsh, went to Miami Beach Police (it wasn’t their case), and spoke to an FBI agent in its Miami office. His sister Sondra even called Milwaukee Police and talked to them at length. They promised to call Willis but never did. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to get a Herald reporter and a local TV news person interested.

His press room friends began to tease him. When other serial killer stories hit the newspaper, they’d ask, “Willis, did you see this guy too?”

Much later, he said, he watched John Walsh do a segment on America’s Most Wanted about a child kidnapped from a Kansas shopping center. “He said, I can sympathize, that happened to me, and no witnesses came forward.

“I called the show to say, I came forward. But they hung up on me. I called three, four times, and each time they got rid of me, like I was some kind of nutcase.

“I’ve always been so certain it was Dahmer because of the face, but they convinced me of the hair. Who knows? Maybe he didn’t have long hair. I remember the eyes, the facial features. Maybe I got confused on the hair.

“I’m positive about what happened, how he approached me, what he said, and that I followed him to the toy department. Plus his eyes. Unusual eyes. The look.

“I stared at him about 15 seconds. I could be wrong about the hair.”

Curious about this point of doubt, I called back Ken Haupert Sr. to ask about Dahmer’s hair.

“He always needed a haircut,” he said. “It was long in the back. I kept telling him to comb it.”

I also asked him if he’d ever seen Dahmer angry. He said he didn’t have time to get into it, but yes.

“I saw hell in his eyes, once,” he said.

That sounded like Morgan’s description, too.

Carrying library books with still photographs of Dahmer plus tape of an A&E documentary about him, I visited Morgan at his ground-floor apartment in the triplex he owned. He was 55 with thinning blond hair and large eyeglasses, from Long Island, N.Y. – on the phone I thought I’d heard New England. I saw how his gait was affected by his leg prosthesis.

In the mall that day, he explained, “If I’d had two good legs, I wouldn’t have been so nervous.”

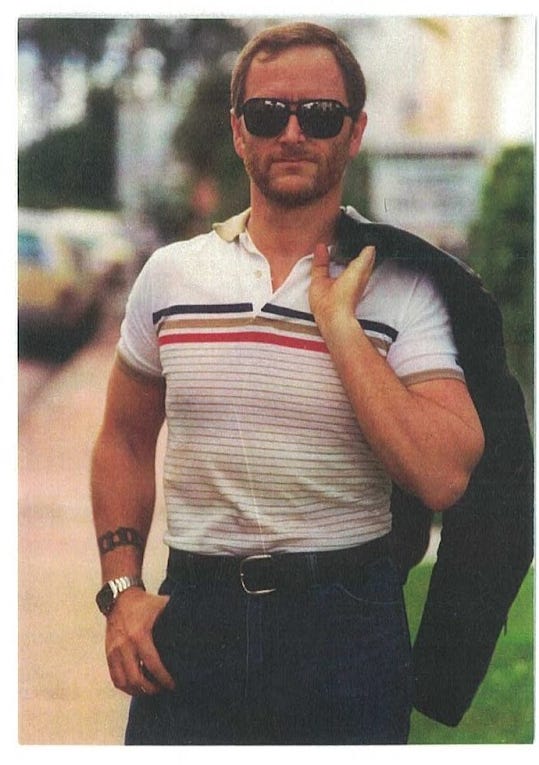

My first impression of Willis was kinda frumpy, and I wondered to myself why Dahmer would have been interested in him. [Willis did not appreciate that description when I wrote it in my book. “Frumpy, grumpy,” he complained.] But I think he picked up on this and showed me a photograph of himself, circa 1985.

The difference was striking. In the photo he looked – and even posed – like a male model. He wore a skin-tight polo shirt over a well developed chest. His hand over his shoulder held a windbreaker, and he wore dark sunglasses.

In advance I apologized for asking about his sexual orientation, but I explained it was relevant because in the photo he clearly matched a type that Dahmer had often repeated he’d sought out. Taking no offense, he said he was hetero.

In his 1992 interview with Jack Hoffman, Dahmer spoke about the kind of men he was looking for, to pick up:

The police transcriber didn’t get it right – Dahmer was referring not to the cartoon chipmunks Chip and Dale but to the well-built male strippers who in the Eighties performed (mostly) for women at a famous chain of clubs called Chippendale’s.

“I think I was his first choice. He went into the toy department, looking for somebody else.”

I showed him a color news photo of Dahmer walking to his first appearance in Milwaukee County Court.

“That’s the guy,” he said.

Later, watching the A&E show, in which Dahmer wore a red prison jumpsuit, he added, “There’s no doubt in my mind.”

One of the books had another Dahmer mugshot, also from 1982, not wearing glasses. “That’s him – with longer hair. I swear to you, when I look at the guy, that’s the guy.

“I’m looking at his eyes, his face. We made eye contact – we locked. It was frightening.”

On the videotape was footage from the trial. Dahmer hadn’t testified in his defense, but at sentencing he spoke to the judge in an attempt to humble himself. I’d hoped Willis could similarly identify his voice, but his reaction wasn’t nearly as certain.

“That could definitely be the voice. But he’s sober.” At the mall, he said, Dahmer had been drunk, and was in a completely different mental state than in court. “I’m trying to give the most honest answer – it’s not the same situation. He was loud and aggressive. Reading that speech, he was docile.”

In 1992 he’d had a similar thought about listening to Dahmer, in person. When Hoffman told him he was going to interview Dahmer in Milwaukee, Willis asked if he could go too, so he could hear Dahmer say, “Hi there, nice day, isn’t it?” Willis even proposed to pay his own way. He said Hoffman told him, “That’s not going to happen.”

After the interview, Hoffman called him back. He said Dahmer had looked him in the eye and “was very, very frank with me. He even told me, I’ve got nothing to lose. If I did Adam I would have told you. And I believe him.”

Still, Morgan insisted he’d seen Dahmer and asked for a polygraph test.

“Listen, Willis, Jeffrey said he was working 10 hours a day, seven days a week and never took days off. Every once in a while they would just give him a day off. He was sleeping on the beach, didn’t have a vehicle, and was drinking heavily.” He added, “That little kid doesn’t fit his M.O.”

When Morgan heard that Dahmer had been killed in prison, “my heart sank because I knew nobody would ever believe me.”

Although Morgan had left his Herald job more than five years before I found him, he wanted me to speak to people he’d worked with and who remembered his story. He guided me to Richard Herland, who told me he hadn’t spoken to Willis since he’d left but vouched for his credibility and sincerity, and remembered when Dahmer’s photo had made the Herald in 1991:

“He’s definitely sane, and definitely telling the truth of what he saw. Every time I heard the story, it was the same thing.”

Bill Bowen, the other witness who in 1991 identified Dahmer at Hollywood Mall, was also easy to find. In an online phone book, he was listed as living in a suburb of Birmingham, Alabama. Like Morgan, Bowen also seemed to be waiting for my phone call. He told me that a year earlier he’d emailed America’s Most Wanted, and although as a cameraman and director of production he’d once shot a segment for them, “nobody was very interested.”

“I was there at Sears. To see how violent he was, it wasn’t normal. I saw him take the kid up by one arm, like he was a sack of potatoes. He violently threw him into that car.”

Car?

In 1991, I said, he’d told Hoffman he’d seen a man throw a child into a blue van.

There had been a blue van nearby, he said, which screeched away. He described the car as big, white or offwhite, with a Florida license plate with the letters BAC or VAC. “I was distracted by the blue van – which may have had nothing to do with the white car.”

In his 1991 statement, Bowen hadn’t mentioned any car, much less one that sounded like Ottis Toole’s Cadillac. And BAC or VAC were the letters he’d said were on the blue van’s plate.

I shut up and let him go on.

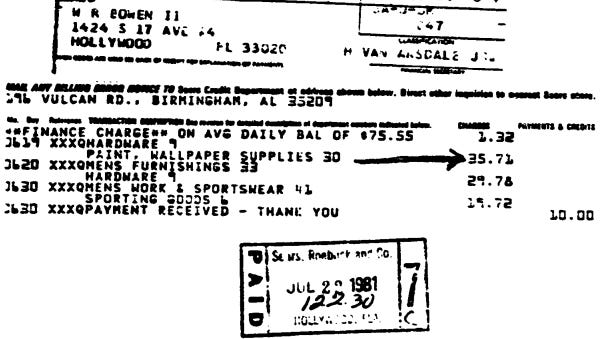

After finishing college in Alabama, he said, in 1980 he’d come to Hollywood to take a job at Calder Race Track, in north Dade County. He stayed only eight months before returning home. On the day in question, he went to Hollywood Mall to pay his Sears bill, which he did in the moments after the incident. He remembered getting his statement time-stamped, but in 1991, ten years later, he couldn’t find that month’s statement.

I didn’t say this then, but in 1991 he’d said something different:

He’d paid the bill earlier, on a Wednesday, and said he’d returned to the mall five days later, to browse.

In 1981, he didn’t immediately tell police what he’d seen because it took a few days to realize its possible significance. “I saw a missing poster at a Kentucky Fried Chicken drive-in, near the mall, and that’s when I thought, maybe I saw what happened.”

At that time, his apartment had been burglarized and his college ring stolen. Hollywood officers had responded; he told them what he’d seen at Sears, and they promised to pass it on to the case detectives. He got no callback, though.

Already upset at South Florida’s violence – in 1981, homicides hit an all-time peak – his apartment break-in was the last straw. He impulsively resolved to go back home, and quit his job. “I literally loaded up my car one night and left.” He thought he was back in Alabama when Adam’s head was found, but didn’t know about it because he didn’t see the story in the local papers. He finally read it several months later.

Two years later he read that Hollywood had solved the case. “Then I found out that they hadn’t.” That was in 1991.

Talking to me, Bowen said he felt tremendous pain because he hadn’t done more to tell police what he’d seen. “I feel to this day, if they [the officers responding to the burglary] would have taken this seriously, something would have happened.”

In 1991, after giving his taped statement, he said Hoffman told him, “Thanks for helping, but we have our man.”

I had Bowen start again from the beginning. He said the incident had occurred near Sears’s customer pick-up entrance, which had a carport. That was on the Hollywood Boulevard side, the south side, facing the police station. But he’d told Hoffman he’d parked on the west side and his car was facing south:

He told me he thought the time was around lunchtime because he had to be at work at the racetrack between 12:30 to 1 o’clock. From the mall to Calder was about 20 minutes’ drive. To Hoffman, he could not recall the time:

But he also told me that Monday was his day off. On a Wednesday, like July 22, he might have been at Sears around noon.

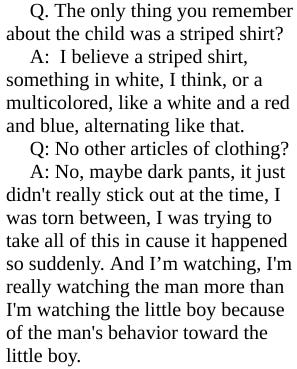

He described to me the small boy he saw as maybe five years old, wearing a funny hat – he couldn’t describe it any better because he saw him from the back. He was wearing dark-colored shorts – blue, he thought, and a polo-type shirt of which he couldn’t recall the color.

To Hoffman he’d said the child was about five or six and had straight hair and what looked like a Chinese bowl haircut. He didn’t mention a hat:

The man he saw had a balding spot on the back of his head and his pants were splattered with paint. “He was nuts. He turned toward me. He reminded me of David Letterman – the way he had a gap between his teeth.”

I said he seemed to be describing Toole. He agreed. “It looked like Ottis Toole – from what I’ve seen of him.”

These photos of Toole, published the morning after Hollywood’s 1983 press conference, seemed to show a bald spot and a gap in his teeth:

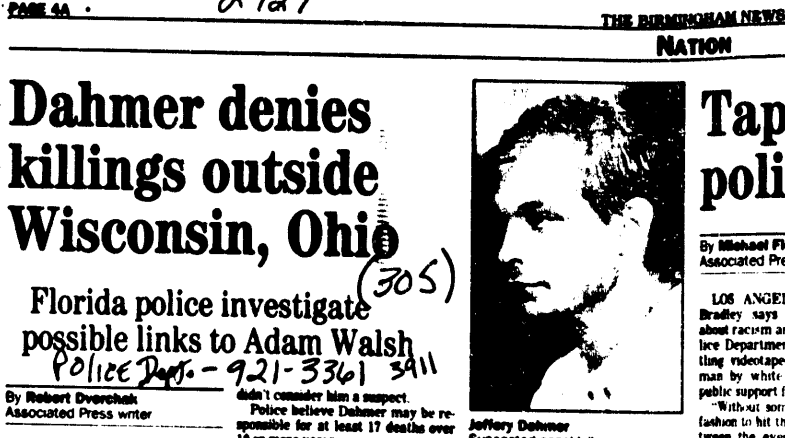

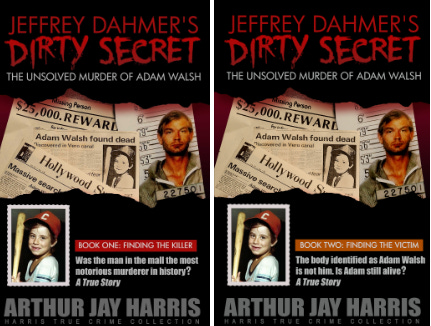

Okay, enough of this. I read Bowen the transcription of his words to the police: he said he’d seen a blue van leaving, with a screech. And the man who he’d seen throw the child into the van resembled Jeffrey Dahmer, whose photograph he’d just seen in The Birmingham News.

He didn’t believe me. He insisted the newspaper story had been about Toole.

But I had the clipping, printed from the police microfilm. I read him the headline: Dahmer denies killings outside Wisconsin, Ohio. And its subhead: Florida police investigate possible links to Adam Walsh. It had a photo of Dahmer. And handwritten on the clipping was the phone number for Hollywood Police.

He still didn’t believe me. Look it up on microfilm in the Birmingham library, I said. I gave him the date – Sunday, July 28, 1991. Page 4A.

A stunned silence followed. Bowen didn’t sound like a flake. He was 44, a media professional like myself, and state university-educated.

“Maybe I was confused,” he conceded, trying to save face. “It shocks me to think... the only name I remember was Ottis Toole.”

Turning off any trial attorney bluster I incidentally might have shown him, I began probing why he might have replaced references of Dahmer with Toole.

He thought he knew: he’d recently read Tears of Rage. For years he’d resisted, thinking it would alter his memory. He’d looked in the book for his name, thinking Walsh might have criticized him as a witness who hadn’t done enough at the time to help.

His name wasn’t there. For that matter, Walsh mentioned Dahmer only briefly while concluding that Toole had killed his son. Toole was in the photo section, severely gap-toothed and badly dressed.

“It all happened in ten seconds,” he explained.

Oh, man, was this any good at all?

I knew who to ask: Brian Cavanagh, the chief homicide prosecutor in Broward County. I’d written my first book about one of his cases, and kept him up to date with my progress on this one. Did Bowen’s reversal ruin his credibility?

No, he thought, he could be rehabilitated.

He suggested I mail Bowen the full transcript of his police interview in 1991, plus the Birmingham News clip. It was crucial to the case, he said: “He is the hub of the wheel in which all of the circumstantial evidence comes together.” (Brian had become my friend; he actually talks this way. Sometimes.) Without Bowen’s blue van, he said, Dahmer’s access to a similar vehicle at work didn’t matter.

Back to the online phone books, I got Bowen’s address. I mailed him the pages – and a letter apologizing for the intrusion. I waited a week to call him and left a message, then reached him the next night. He said the night before he’d reluctantly read what I’d sent.

“It was eye-opening,” he said.

As I’d guessed, the handwriting on the newspaper clipping was his. Yes, now he remembered, it was about Dahmer.

As he’d said in 1991, he’d only seen a blue van. He explained: “After I read the [Walsh] book, it tainted my memory and I saw a white car.”

He still thought the man was gap-toothed. But talking more, he agreed, the book might have affected that impression, too.

What he remained certain of was that he’d seen a man who’d “lifted a kid by one arm, kicking and screaming, and slung him into the vehicle.” Later he described the throw as “like a pendulum,” with a windup. The throw itself, when the child hit the inside wall of the van, must have injured or even killed him.

“That’s something you will never, ever forget. My memory of all this is very vague. Certain points I do remember; other points, I don’t know.”

On the abduction itself, I noted, he was consistent from Hoffman’s 1991 interview to mine.

“The guy was nuts, out of his mind, he was raging. He turned around for just a brief moment. I was scared to death. How could a father treat his child like this? Others around me were in shock, too.

“At the time I remember a blue van – it was nondescript. I read the book, thought maybe I’m wrong, it was a white car.”

I thought, Willis Morgan had said when Hoffman told him that Toole was the prime suspect, Morgan had questioned himself whether he’d really seen Toole.

A van is higher to the ground than a car, I reminded Bowen. You just told me the man lifted up the kid.

He agreed. “He had to lift the kid up into the van. Big blue van. Held him up. Threw him in, peeled off.” Later he added that the van sped off almost before its door was closed. In its dust was the smell of burning rubber.

Did that suggest there was a second person in the van, a driver?

I asked if he could say for sure he’d absolutely seen Dahmer. He wouldn’t commit – but he hadn’t said that in 1991, either. I offered to email him Dahmer’s August 1982 mugshot.

Days later, Bowen called me. “It doesn’t ring a bell. But I saw the guy from the back. He turned around [for just a moment]. At first I thought it was an angry parent. Looking back, I’ve never seen a parent like that. Maybe this wasn’t an angry parent.”

Within the last year, he said, he’d watched an MSNBC documentary about John Walsh, which I’d seen too. After that he’d emailed America’s Most Wanted asking, is this solved or not? He then re-volunteered his information.

He got a callback from someone who said he represented the Walsh family. He’d said he’d follow up, but no one ever did.

“I don’t know how to make this right. I have a lot of guilt that maybe I could have helped more.” At that moment, he added later, “I didn’t think evil. Why would somebody abduct a kid in broad daylight? It just didn’t cross my mind. It’s been a thorn in my side all this time. What could I have done differently?”

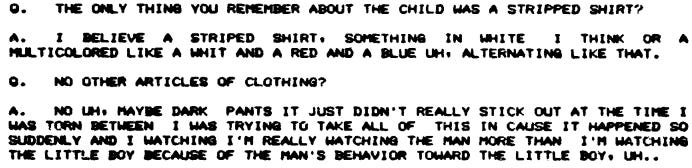

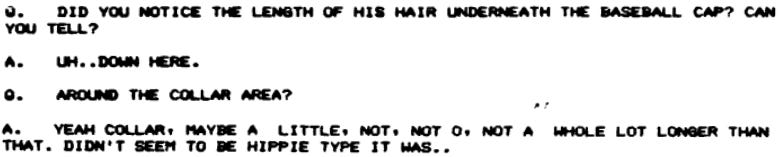

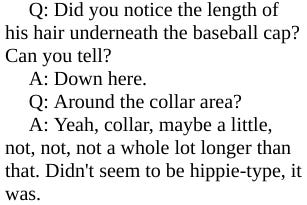

There was a question I missed but Hoffman had asked. Bowen had said Dahmer was wearing a dark blue baseball cap:

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 28: The unluckiest man in the story is also the luckiest

You’re really far now, you’ll want to keep reading, there’s so much more about this story you had no idea about. And now we’re deep into the Jeffrey Dahmer section. FOLLOW, or SUBSCRIBE now for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. But if you’re the type who pays for subscriptions on Substack, maybe you might consider me too? (I wouldn’t mind in the least.)

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular, #investigative

‘Officer Elvis’ and ‘Officer Presley’ I would have loved to meet! :) Bowers changes his story from seeing a man with a bald patch to a man wearing a cap. And the rest. That picture of Willis in the 80’s, such a throwback!