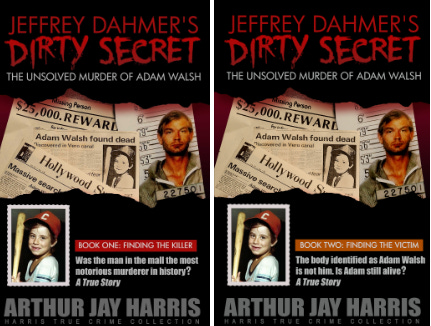

The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 10

Part 2: The First Two Weeks; Episode 10: The Day They Found Adam

Link to Episode 9: For why the autopsy report was missing, there was no explanation — or excuse.

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Police had found one witness, a 10-year-old boy, who said he’d seen Adam next to a blue van parked just outside the Sears store, and then disappear.

Police asked everyone who’d seen a blue van anywhere in the area to call them.

After the police determined that everyone had searched everywhere in Hollywood, the Walshes broadened the search beyond the city. Two weeks after the disappearance, with the Walshes still a daily constant in the local press, they got booked to appear on a national show, ABC’s Good Morning America, in New York. Charlie Brennan, the reporter from the Hollywood Sun-Tattler who was on the story from the first day, went with them.

In the early evening after the Walshes arrived in Manhattan for their next-morning appearance, back in Florida two men loading their fishing boats into a highway-side drainage canal more than a hundred miles upstate, in a swampy rural area west of Vero Beach, saw something floating on the surface. They’d first thought it was a doll’s head but on closer look, it was a child’s. They worked for a citrus farm and from their vehicle, radioed their office to have them call the Florida Highway Patrol. Hours later, thinking it might be the boy Hollywood Police was looking for, the sheriff’s department in Indian River County called them. The local fire department took the remains from the water and brought them to the regional morgue in Vero Beach.

It was then late at night and Hollywood Police decided to send its detectives to the scene before alerting the Walshes. Anyway, the answer to where they were was on the top of the front page of that afternoon’s Sun-Tattler: New York. Hours later, in the predawn, Indian River County Sheriff’s Sgt. Rick Baker called the show to find them and was told the name of their hotel. He recalled the conversation ten years later:

Walsh spoke to the lead Hollywood detective on the case, Lt. Richard Hynds, who asked him if Adam had a dentist. The show producer called the Walshes and offered to get them on the first morning flight out so they could go to the morgue. No, John said, we want to stay, we want to do the show.

Later, at the studio, host David Hartman offered him the same, they didn’t have to go on, but again, John declined. After Adam’s dentist’s office would open in the morning and police could get his records, Hynds himself would take them to the morgue, with the Walshes’ close friend John Monahan.

The Walshes were scheduled to go on at 8:15. Just before the end of the show’s break at the top of the hour for news and weather, John called Hollywood Police. They told him that the officers on the scene in Indian River County thought that the head was almost certainly Adam’s.

On John, all eyes:

Reve. Charlie Brennan. David Hartman. The studio production crew. The news and weather was done, a block of commercials was running, and the show had to prepare for the next segment. The executive producer told John they could still back out, they had something for emergencies they could use to fill in.

No, John said.

Then if they’re going to do the segment, Hartman said, he had to ask him about the latest news, what the police were saying. John said okay.

It was time to lead the Walshes onto the set.

On air, Reve looked catatonic. She wouldn’t say a single word:

With as much deference as possible, Hartman asked John right off what the latest news was. Years later, Larry King re-aired tape of how John Walsh had answered:

After Walsh spoke that, Brennan immediately called his city editor in Hollywood to say that Walsh did not believe what he had just said.

When the segment ended, the show cut away for local news inserts. Behind the set, alone, John told Hartman, “It is Adam’s head they found.”

“We both cried,” Hartman told me, decades later. He remembered it excruciatingly well, he said it was his most difficult moment in television. They stayed there for 30 seconds or a minute. “But I had to finish the show.” I asked how he did that. He answered, “I don’t know.”

Past 9 o’clock, Lt. Hynds picked up Adam’s dental chart, then met John Monahan. To drive to Vero Beach they would take the Florida Turnpike, and at 100 mph or whatever they could get there in a little over an hour. But they didn’t take a police car; the lieutenant rode with Monahan in his white Mercedes convertible, driven by Monahan’s chauffeur, Hynds told me.

11 A.M.: Monahan and the lieutenant arrived at the morgue, which was a portable trailer. Hynds handed the medical examiner the dental chart: Adam had a filling in a lower left molar on the cheek side. So did the child on his table.

The M.E. asked Monahan whether he could stomach a look at the remains. He said he could do it.

The room must have been claustrophobic, not to mention the smell of decomposing flesh. It was a hell that in some ways, once entered, you couldn’t ever leave. It was the last place in the world that anyone would want to visit at that moment.

This is from Walsh’s book:

Walsh did not name Monahan as the identifier, but in this passage he indicates that on his first sight of the remains, he was uncertain. He said he’d just seen Adam days before he’d disappeared, two weeks earlier, and Adam had smiled at him. In a news story about the search, he’d described himself as a family member:

Nor did Walsh describe which tooth was emerging in the mouth of the child Monahan said was Adam.

Descending the stairs – in this case, Hell had been steps up, not down – a Miami Herald reporter photographed him.

Ten years later, Hynds spoke about it:

In New York, Charlie Brennan stayed close to John Walsh, in his hotel room by the telephone, waiting for news. Reve had decided to go to breakfast and take a walk. His paper was holding its press run, and at 11 it was already an hour past its hard, 10 A.M. copy deadline for the afternoon home-delivered edition. I know the deadline because I used to work there. Once, I turned in copy at four minutes after 10. That wasn’t a good thing.

Five years later, after he’d left South Florida to work on a newspaper in Denver, Brennan recalled the moment in a story for his old paper:

At about 11:30, Walsh heard confirmation, Brennan next to him. At this moment, the worst of his or anyone’s life, how could Charlie leave this man alone? But he had to go and call in the story, composing it on the fly, everyone at the newspaper was waiting for him, that was why he was there.

The copy desk scrambled to change its front page. Its headline was simple and dramatic. The hometown paper was first in print with the news:

That afternoon, the remains were flown by a Miami TV news helicopter (with a Hollywood Police officer onboard) from Vero Beach to Fort Lauderdale so the medical examiner there could do the autopsy.

The ongoing airline traffic controllers’ strike delayed most flights that day, and the Walshes didn’t arrive home to Fort Lauderdale until eleven that night. For all the gathered news cameras and print press at the airport’s Delta Airlines counter, they held a wrenching press conference.

In his Larry King interview in 2003, John Walsh remembered it this way:

And so on…

The Fort Lauderdale M.E., who did the autopsy, told the news media that Adam may have been dead since soon after he disappeared. The family held a funeral service; the casket was empty so the medical examiner could keep the remains as evidence. The police were inundated with tips about blue vans until they later decided that the 10-year-old who said he saw it was wrong about the time. They had no other witnesses who saw Adam leave the store that day.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 11: What kind of monster would cut off a child’s head?

The timing is uncanny! Just as they were preparing to go on TV, the remains are found. And they prioritise TV anyway:) It would be interesting to see what the police reports say about the leads on the van.