The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 42

Episode 42: It’s Better in the Bahamas

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

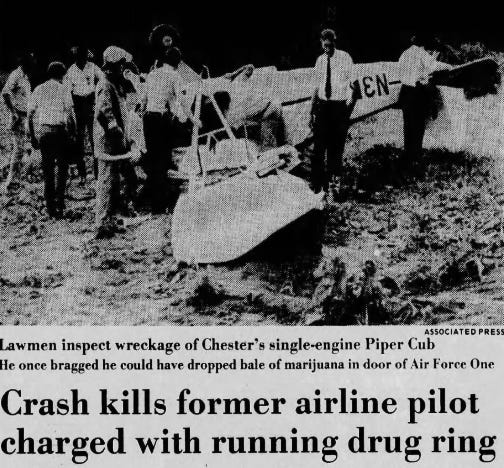

In June 1985, weeks before his federal trial was to begin, Lamar Chester crashed his single engine Piper Cub while flying around his 500-acre chicken farm in North Georgia, which had a landing strip. He was apparently low on fuel, clipped a tree, flipped in the air and landed upside down in the dirt. Chester was killed and his 5-year-old daughter was severely injured, but survived. There were no weather issues and it happened in daylight.

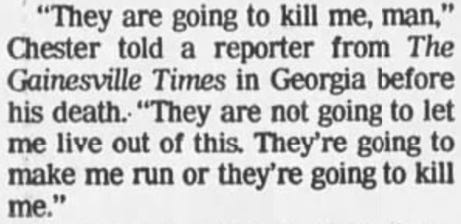

During an interview with Atlanta TV station WAGA, Chester had vowed that even if convicted he would never submit to going to prison. And he told a newspaper reporter that government agents were going to murder him:

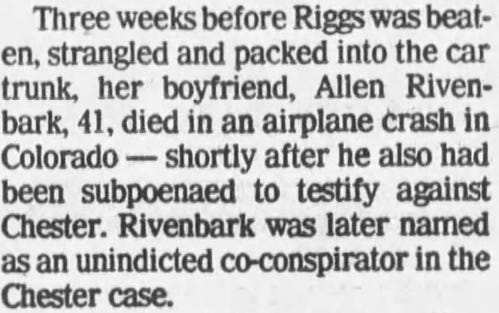

Allen Rivenbark had testified to the Lone Star grand jury in Houston investigating Chester, it had already been reported, but The Tennessean wrote that he’d also been subpoenaed to testify to the grand jury in Atlanta:

A Bahamian committee of inquiry had asked Chester whether he knew Rivenbark, and in answering he mentioned Sibley Riggs:

Boats? Plural?

That suggested Riggs was in deeper than it may have appeared previously.

Elsewhere, Chester said he’d introduced Riggs to Rivenbark:

Could Chester have been behind the murder of Riggs?

Notice a pattern in the case of girlfriends in jeopardy: Monahan’s fiance, Shelly Stock, was on the plane with Rivenbark when it went down. Lesley Bickerton felt threatened by Chester and testified to his grand jury. And Rivenbark’s girlfriend, Sibley Riggs, was murdered.

Or even Rivenbark’s death? Chester assumed Rivenbark’s position in the smuggling ring.

A U.S. Marshal confirmed that about Rivenbark:

Maybe Rivenbark’s plane did go down because of an accident – low fuel, bad weather and visibility, dusk, and it struck a mountain. But given Rivenbark’s sounds-like cooperation against others in his ring – to include Chester – maybe someone was going to kill him, anyway?

Riggs sold yachts to Rivenbark and Chester, and was intimate with Rivenbark and close to Chester. Besides Chester, who would have had an interest in her not appearing at the grand jury? Rivenbark was already dead.

Okay, now, who would have actually done the hit?

1981 was one of the two peak years for murders in South Florida. Even though two of my other 1980s true crime book stories from here have hired hitmen, I could be wrong but I don’t think there were lots and lots of them here, in part because their careers tended to be short, with abrupt endings. Big Jim Capotorto was killed in 1976. Even if Ken Ogawa had an assignment to kill Rivenbark, Ogawa was dead in November 1981.

Police information had Bert Christie killing Johnny Irish Matera, at the end of July 1981. Mobster William Genco, killed in mid-September 1981 and left in the trunk of his car at Fort Lauderdale airport, in that way matches Riggs’s murder three months later. The alligator-bitten private detective was killed at the end of September 1981 and left in the Everglades – that might match Gil Fernandez’s 1983 triple murder, those men also left dead in the ’Glades.

Whew! Still, busy six months for hitmen!

Now let’s continue on our speculative path, to Monahan, who Steve Votra said was also fucking Sibley Riggs:

At the last moment, Monahan decided not to board the doomed flight – although he let his fiancée Shelly go on, and he knew the other passengers, including the pilots. He may not have known Ogawa.

Was this just a lucky twist of fate for Monahan – or did he know something?

It’s hard to think that he got a last-minute word that the plane would be sabotaged and didn’t try to alert Shelly or his other friends.

Still, Monahan is a wild card. If he was banging Sibley, would that suggest he also had a financial relationship with her? Monahan was in with Rivenbark to some extent but if there was more to it than we know, might Monahan have been a person of interest to the Lone Star investigation? And then, might her upcoming grand jury testimony have been a threat to him?

Or might Monahan have been cooperating, too?

I said I was speculating. And as I said before, Monahan died in 2004.

And at long last, let’s come back to John Walsh.

In his book, rather than ignore any allegations said or unsaid that he’d touched the smuggling trade, he seemed to go far afield to raise them himself so he could deny them. He wrote that in 1996 he asked Hollywood Police Chief Richard Witt to tell the press:

But Monahan had a drug-related association.

So, again, the big question – Who would kidnap a young child?

In the first week, Walsh told the Sun-Tattler that Adam could have been taken by “a lonely older person” who wanted a child of their own. But when the child’s head was found, that ended that idea.

One remaining possibility was a family dispute, like leading to Jimmy Campbell:

But Campbell as a suspect never rang true to me, again considering the severing of a child’s head. And days after it was found, Lt. Richard Hynds seemed to agree:

Medical Examiner Ron Wright had disagreed with Hynds ever so slightly. He told the Herald:

But if that was what had happened, it would have been very unusual.

Say what you will about Jimmy Campbell, he wasn’t going to strike again.

Yet there was another possibility which neither of them had mentioned: Given the time and place, South Florida in 1981, the kidnapping and beheading of someone’s child could have been about someone sending a message.

That someone, and the receiver, would have been in the drug trade and/or the Mafia.

And what would the message have been?

Don’t fuck with us.

Or maybe more specifically:

Don’t testify against us.

There were reported rumors about John Walsh. I heard them too, but they were just rumors, they never went anywhere. Whenever I asked, Where did you hear that from? I never once got a real answer.

To me, those were the only two possibilities – sociopath or mob message. Hollywood Police spent too much time on Campbell and none that there’s a public record for on Operation Lone Star.

Walsh wrote about working in the Bahamas in the mid-1970s:

A little later, I’ll get back to Walsh’s former friend Bill Collins, who worked with Walsh and Monahan at GAC Resorts, a division of a huge vacation-home land sales company. Collins told Jack Hoffman that Monahan got Walsh the job in the Bahamas, or made him the introduction, as he’d done for all the tourism-related jobs where Walsh worked.

Walsh left this out of his book and story narrative, also:

Bahamians quoted by The New York Times believed the percentage was much higher:

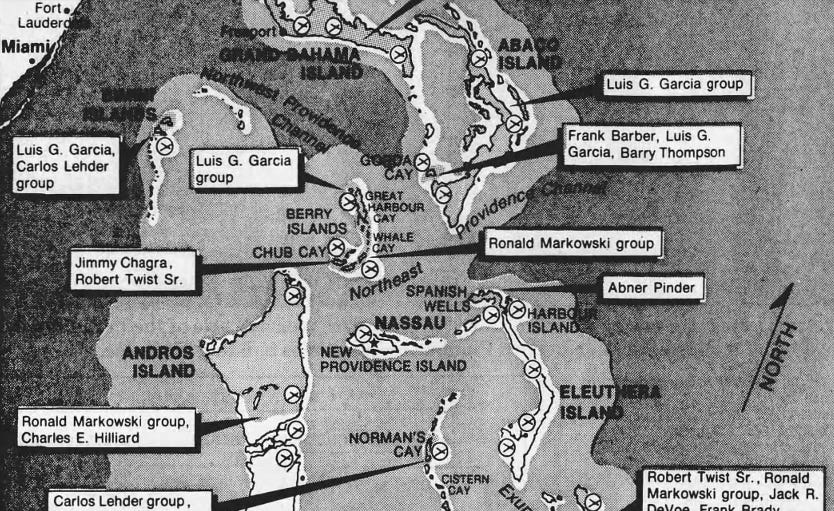

A Herald map showed how the 700-island chain had been divided up among smuggler groups, also noting locations of airstrips. From Miami, in the upper left corner, it’s just 50 miles to the closest island, Bimini:

Could anyone working then in the tourism business in the Bahamas not know that smuggling was happening in the smaller “out-islands,” and that proceeds were being laundered through the mob-controlled casinos and banks on the bigger islands?

Back to the first days of the story:

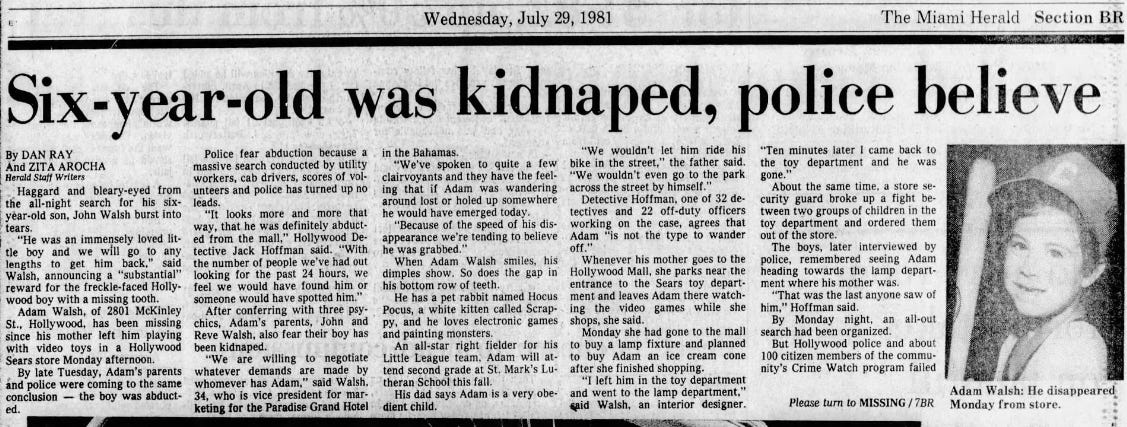

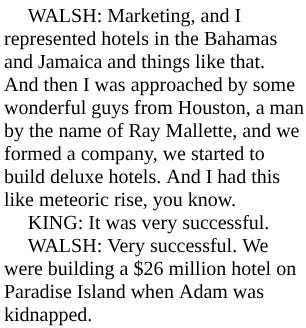

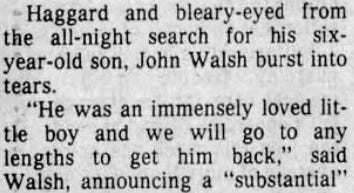

The Hollywood Police Department’s entire detective bureau – 32 detectives, plus 22 off-duty officers, all on mega-overtime, up to 80 and 90 hours a week for the next two weeks – looked for Adam. Helping them was the city’s hundred-member community crime watch group, which gathered at the police station, then fanned out to search for any clues. But by the end of the second day, when he wasn’t found alive or dead, the police thought that he hadn’t merely strolled away:

Walsh agreed. “We are willing to negotiate whatever demands are made by whomever has Adam,” he told the Herald.

Possibly it was the police who first asked Walsh about it, but in newspaper interviews he himself raised the idea that the kidnappers hadn’t taken Adam at random:

Did Walsh think that the kidnappers may have known who he was or where he worked?

Was he, as he said, a normal working father?

The hotel was a huge project:

Why would anyone who would know enough about him to know that he had a young child – think that he was an owner of that hotel?

Less than three months before the disappearance, Walsh had posed for a photo with local travel executives and a Playboy bunny at an event at the Miami Playboy Club. The picture ran in the Herald’s Sunday travel industry column:

But in 2024, after the Fox network renewed Walsh’s original show “America’s Most Wanted,” a Fox website reported that he had been a hotel developer:

But in fact, only about a week after he’d told the South Florida press that he was just a working man, on a trip to meet with out of town news media to promote the search, an Orlando newspaper described Walsh as a hotel developer:

Five years later, in 1986, The Miami Herald described him as a “former hotel builder”:

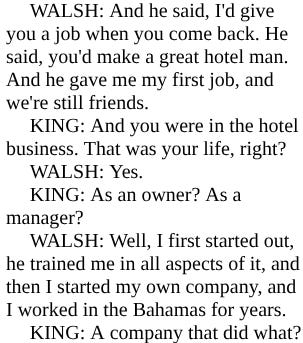

In 2003, interviewed by Larry King on his CNN show, Walsh first talked about how he’d met John Monahan at the Diplomat Hotel:

There was another anomaly, as reported in the newspapers. This was the Herald’s first-day lead:

The quote was very curious. By using the past tense it sounded like Walsh thought his child was dead – then he caught himself.

Did anyone notice that? The Herald reporters and editors apparently did.

He gave a similar quote to the Hollywood Sun-Tattler for its morning edition:

Even the next day, Walsh still spoke of Adam in the past tense:

What was John thinking that he didn’t share with the press, or possibly the police? Do these long forgotten quotes mean little, or are they overlooked clues that should have been followed?

Is this the most famous passage in all of crime fiction literature?

Sherlock Holmes is speaking to Inspector Gregory of Scotland Yard in the story of the missing racehorse Silver Blaze:

Gregory: “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Holmes: “That was the curious incident.”

There was a simple key to solving the case but only Holmes recognized it.

Whether detectors know it or not, this is the central issue in their work, and I raise it in all of my true crime stories: Have the police, the medical examiners, and the news media missed or gotten diverted from the path that solves the crime?

This is what Sherlock Holmes was a master at realizing.

Diversion happens for these reasons: lack of experience or insight; out-and-out incompetence or disinterest; or someone is intentionally trying to divert the detectors.

In all of my stories, I expose clues that official law enforcement and the news media have missed, not dug far enough to uncover, overlooked, ignored, forgotten, or dismissed because they didn’t seem to fit their theories, or challenged their theories.

And then begins an argument, often not rational but instead based on power, position, and authority – and sometimes includes name-calling:

Who’s right?

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 43: South Florida – the sun and fun and murder capital of the world