The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 25

PART 4: Finding Jeffrey Dahmer. Episode 25: You didn’t know him from Adam?

Link to Episode 24: John Walsh abruptly changes his mind: Now he thinks Ottis Toole killed Adam.

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

After publishing in New Times, I put the story down, not expecting to return to it. Five years later, on a Saturday afternoon in the summer of 2002, driving, my mom and I spotted a used bookstore I didn’t know existed. After making a Let’s do it stop, she browsed Mysteries, which she loved, while I looked for the much more boring True Crime shelves. In there I found a book I also didn’t know existed that had a transcript of an interview with Jeffrey Dahmer. It was written by former FBI serial-killer profiler Robert Ressler, who in 1992 was working for Dahmer’s defense team.

I showed it to my mom and explained that Hollywood Police’s Walsh file had a section about Dahmer. He’d admitted he’d been here in South Florida when Adam disappeared.

How closely had I read that section? she asked. Not that close, I said. The newspapers had written that it was kind of interesting that he was a suspect in the case, but the cops had looked it all up and said there was nothing to it.

Maybe you shouldn’t have trusted the cops so much, she said.

Umm…

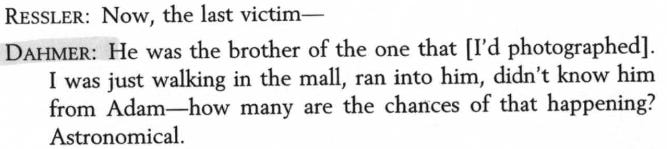

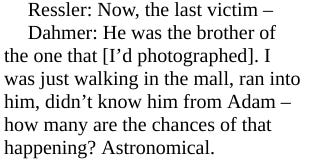

If there was anything relevant in the interview, I decided, I would buy the book. Reading it in the store, it was kind of a softball interview, mostly junk, Ressler didn’t challenge Dahmer at all. But there was one thing:

Dahmer was talking about finding his last Milwaukee murder victim, 14-year-old Laotian-born Konerak Sinthasomphone, the younger brother of Somsack Sinthasomphone, who was 13 when Dahmer was arrested for sexually assaulting him three years earlier:

Fuck! Dahmer was a serial killer who severed heads and trolled shopping malls for children to abduct, and six months before this interview he’d admitted being in Miami when the Walsh child was reported lost –

And this child he didn’t know from Adam?

Come on, Ressler, you didn’t catch that? Or since he was then working for Dahmer’s defense, he didn’t want to catch it?

And how many were the chances that I would have come across this obscure, crappy, out of print self-promoting book and seen this quote? Also astronomical?

Like one in how many zillion?

None of this happens without my mom. On the spot in the bookstore I resolved to re-read, this time closely, the Dahmer section in the Walsh file and learn everything I could about Jeffrey Dahmer. Especially his time in Miami, which wasn’t well-known at all.

I knew that the file had a transcript of an interview Jack Hoffman had done with him. It was on the microfilm reels that Hollywood Police had released in 1996, which I’d used for my reporting up to then. The only place to read them was at the regional public libraries, and back then I’d dropped dime after dime into the coin slots of their printer box vending machines.

I’d borrowed the reels from my friend at Channel 7, who never asked for them back. So I dug them out again, bought a few more rolls of dimes, and trekked back to the library.

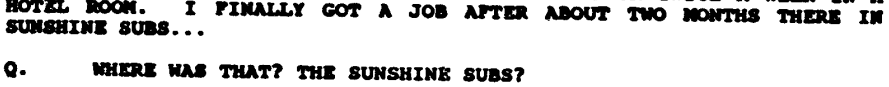

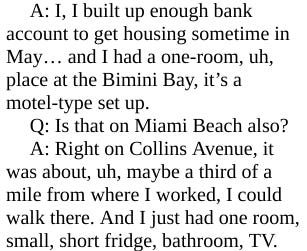

It was August 1992, and Hoffman was hoping that Dahmer would confess to killing Adam. The interview went an hour, covering 40 transcript pages, but it was largely over early when Dahmer denied the murder. The only thing he gave up was that while he was working he fraudulently collected unemployment insurance. Hoffman later checked that and found nothing. A year before, Hollywood had asked three other police departments if they had records of Dahmer: Miami, Miami Beach, and Metro-Dade had all said they had nothing. Nor had Hollywood.

And then, unable to confirm that Dahmer had ever been here, despite his admission, Hoffman gave up – and even wrote that he believed him.

Dahmer’s arrest in Milwaukee in 1991 was ten years after Adam disappeared. I was coming at it another eleven years later. But what I brought to the table was – I wasn’t a cop. And at that point I’d already published three true crime books.

Not boring ones, either.

And by then, like my mom implied, I should have known better than to blanket-trust the police’s judgment.

During the interview, Dahmer had actually given Hoffman a few clues to follow:

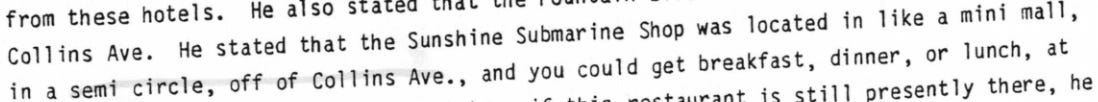

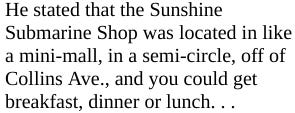

He’d worked for a storefront restaurant called Sunshine Subs.

His boss was Ken Houleb – Dahmer even spelled out his name.

And Dahmer lived for a time at the Bimini Bay motel.

By 2002, when I checked, neither the shop, the motel, nor Houleb were in the current Miami phone book.

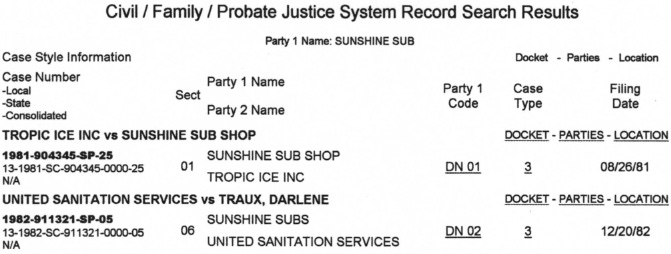

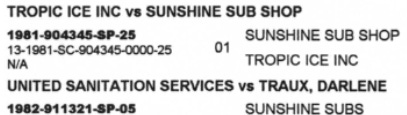

But since 1991, county governments in Florida had built websites allowing online searches of official records. Miami-Dade County posted docket sheets for criminal records, and book and page numbers for civil records. The databases produced nothing for Jeffrey Dahmer or anyone named Houleb. There were hits on Sunshine Subs and the Bimini Bay. During Hollywood’s cursory investigation in 1991, someone had told them the motel manager had since died and its records were destroyed.

Sunshine Subs had three references, from 1979 to 1983. In a small claims action, as a defendant, appeared the name Darlene Traux.

Searching for her, I found no further hits. I tried Broward County records online and also found nothing. I checked the current Miami phone book – nuttin’.

State unemployment payment records weren’t online, so I called Tallahassee and reached a supervisor in Unemployment Compensation’s archives. He said Dahmer’s records would be public but they’d since purged all their paper records dating back that far. Nor was his name or Social Security number in their computer.

Time to go downtown.

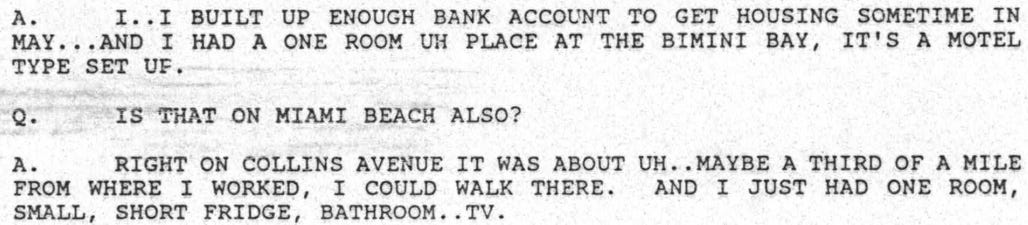

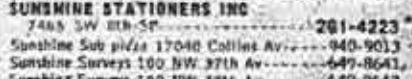

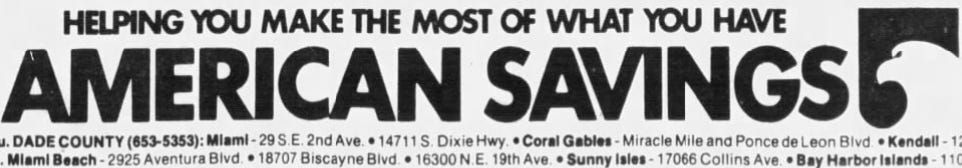

I went first to the Dade County main library’s Florida room, which had the 1981 Miami phone book on microfiche. It listed “Sunshine Sub – pizza,” at 17040 Collins Avenue.

I hadn’t lived far away, so I knew the area. It was in the 170th Street shopping center, which had a dollar movie theater I’d gone to. The Rascal House, which would become the last of the great corned-beef-on-rye delis of Miami Beach and Miami, was a block away at 17190 Collins. I’d certainly gone there, too.

Dahmer had said the Bimini Bay was close to work, and its address in the phone book was 17480 Collins. Also, he’d told Hoffman he had a bank account.

There was an American Savings branch in the strip mall, at 17066 Collins:

And this, too, from the Milwaukee Police report of Det. Patrick Kennedy, dated August 8, 1991:

Yup, the mall is set up like a semi-circle. Okay, Dahmer really had been here.

Once establishing that, it was certainly a coincidence that Jeffrey Dahmer had lived near Hollywood, Florida, when Adam Walsh disappeared, as he said. A child’s head was found and identified as Adam. Ten years later, Dahmer was found with severed heads.

Even if Jack Hoffman couldn’t get a confession from Dahmer, he had two witnesses who said they’d seen him at Hollywood Mall on the day of the disappearance. Yes, it would take more to prove a case against him. But I cannot comprehend how Hoffman could have simply dismissed Dahmer as a suspect based on his denial. At the least, he should have left open the possibility.

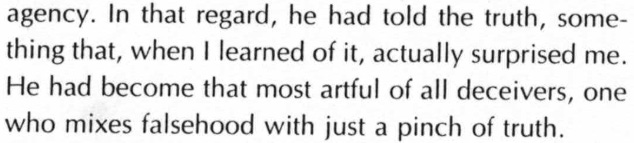

Dahmer was a practiced liar. His father Lionel knew it. In his book, regarding a small point that Jeff had told the truth about, he wrote:

And other things he told, even in Hoffman’s interview, weren’t impossible to prove as lies.

But what Hoffman really should have done was what I began doing, as it turned out, eleven years later. Had he? The Hollywood file doesn’t say so.

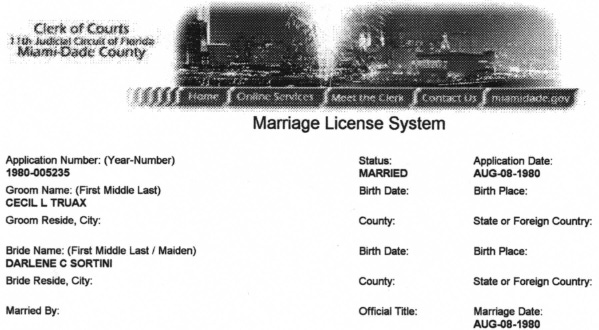

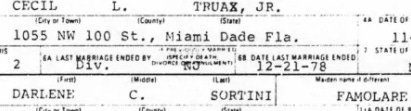

From the library, the county recorder’s office was around the corner. They had a microfilm room of numbered drawers of books and pages – what used to be recorded in physical books. Searching them, I found that Traux was a misspelling – Sunshine Sub’s principals were Darlene and Cecil L. Truax. I searched their names on the county’s computer – and found nothing more.

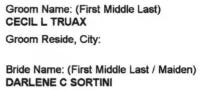

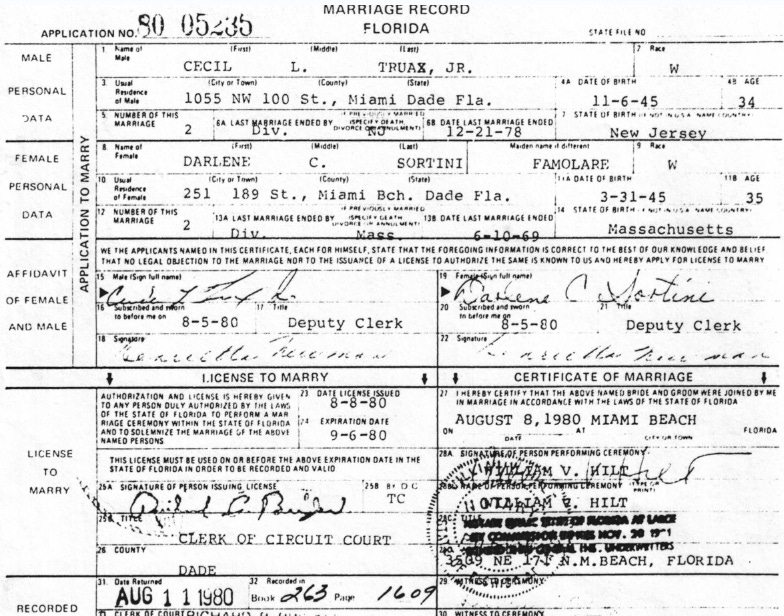

A clerk showed me another database, then inaccessible online, for Miami-Dade County marriage licenses. I got a hit on Cecil Truax: an application number for his 1980 marriage to Darlene C. Sortini.

It was nearly closing time so I raced to another county building, where on a high floor newlyweds-to-be sat patiently for their bakery ticket number to be called, to buy a marriage license. Alone and conspicuously out of breath, at the counter at less than five minutes to five I ordered a photocopy from microfilm of the Truaxes’ license. One dollar and a couple of minutes after five later, the license gave me their dates of birth, both in 1945. Both had been divorced. Cecil Truax was born in New Jersey, Darlene in Massachusetts, and her maiden name was Famolare.

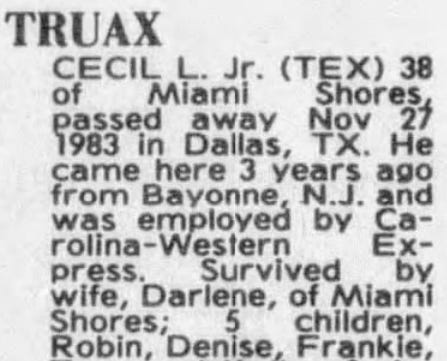

Back to the library’s Florida room, which had a multi-diskette copy of the U.S. Social Security Death Index, 1999 edition. Bad news: Cecil Truax had died in November 1983, his death benefit sent to a Miami zip code. There was no listing for Darlene Truax.

Famolare sounded like a unique name, so still in the death index I found a number of Famolares, all born and deceased in Massachusetts. I guessed, maybe everyone with that name was kin.

The next step was to search The Miami Herald, which by 2002 was electronically searchable by text at local public libraries back to mid-1982, when they’d computerized. I searched for “Cecil Truax” and got a one-line death listing on November 28, 1983. The database didn’t include paid death listings, so I manually searched the library’s Herald microfilm and found one, published the next day. Survivors listed were Darlene, five children, and his two sisters.

That left Darlene as my last tenuous link. But nineteen years had passed; she could have remarried and changed her surname. I had her date of birth, though. How many Darlenes could have been born on that date? I asked my friend Jean Mignolet, a private investigator in Fort Lauderdale, could she run a check?

Eight, she soon replied, but the database had none living in Florida. One was Darlene C. Hill, in Johnstown, Ohio – my Darlene had been Darlene C. Sortini.

Checking online phone books, I found no listing in Ohio for that name. A dead end.

I was down to one last shot. Asking the online phone books for “Famolare” in Massachusetts, I found about two dozen listings. There were none in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, nearby states with large Italian communities.

The next morning, a Saturday, I called the number for Charles Famolare Jr. in Pompano Beach, Florida. The line was temporarily disconnected, which suggested he was a snowbird – it was summertime. But there was also a number for him in Boston. He answered, and I introduced myself as a journalist.

“Hi, I’m looking for a woman I’m hoping is a relation of yours. She was born in Massachusetts and her maiden name was Darlene Famolare.”

Charles Famolare couldn’t have been nicer. “That’s my cousin Darlene,” he said. “She was just here a few weeks ago.” He said the Pompano house belonged to Sonny, his retired dad. He got him on the phone, too.

I explained why I was looking for her – I’d rehearsed this so I could impress them with as much real stuff as I could before I got to the punchline: She’d done nothing wrong, but twenty years earlier, ten years before anyone knew who he was, at her sub shop in Florida she might have hired… Jeffrey Dahmer.

“Dah-mah!” exclaimed Sonny, in an unmistakable Yankee accent. (I’d long ago resolved never to use the word exclaimed in writing, but for this I just broke the rule.) I told them I thought maybe this had been a family joke, that in 1991 Darlene would have recognized Dahmer as a former employee. But the Famolare cousins had never heard this.

Without hesitation and even without asking they gave me Darlene’s phone number – she was Darlene Hill, but in Seymour, Indiana. I called as soon as I got off the phone – I envisioned her cousins thinking, What did we just do? then calling her themselves. I got her voicemail but didn’t leave a message.

I went out for the day and reached her after I got back. By then, of course, her cousins had called, and she was dying of curiosity. She was warm and helpful, and wanted to know how I found her. Had I called several weeks earlier, she said, she was at the funeral for her cousin Ricky Famolare, a sergeant of detectives for the Boston P.D. Their last conversation had been about the Boston Strangler, one of Ricky’s pet interests. In their old neighborhood, growing up, their friend’s Uncle Albert was Albert DiSalvo – the suspected Strangler.

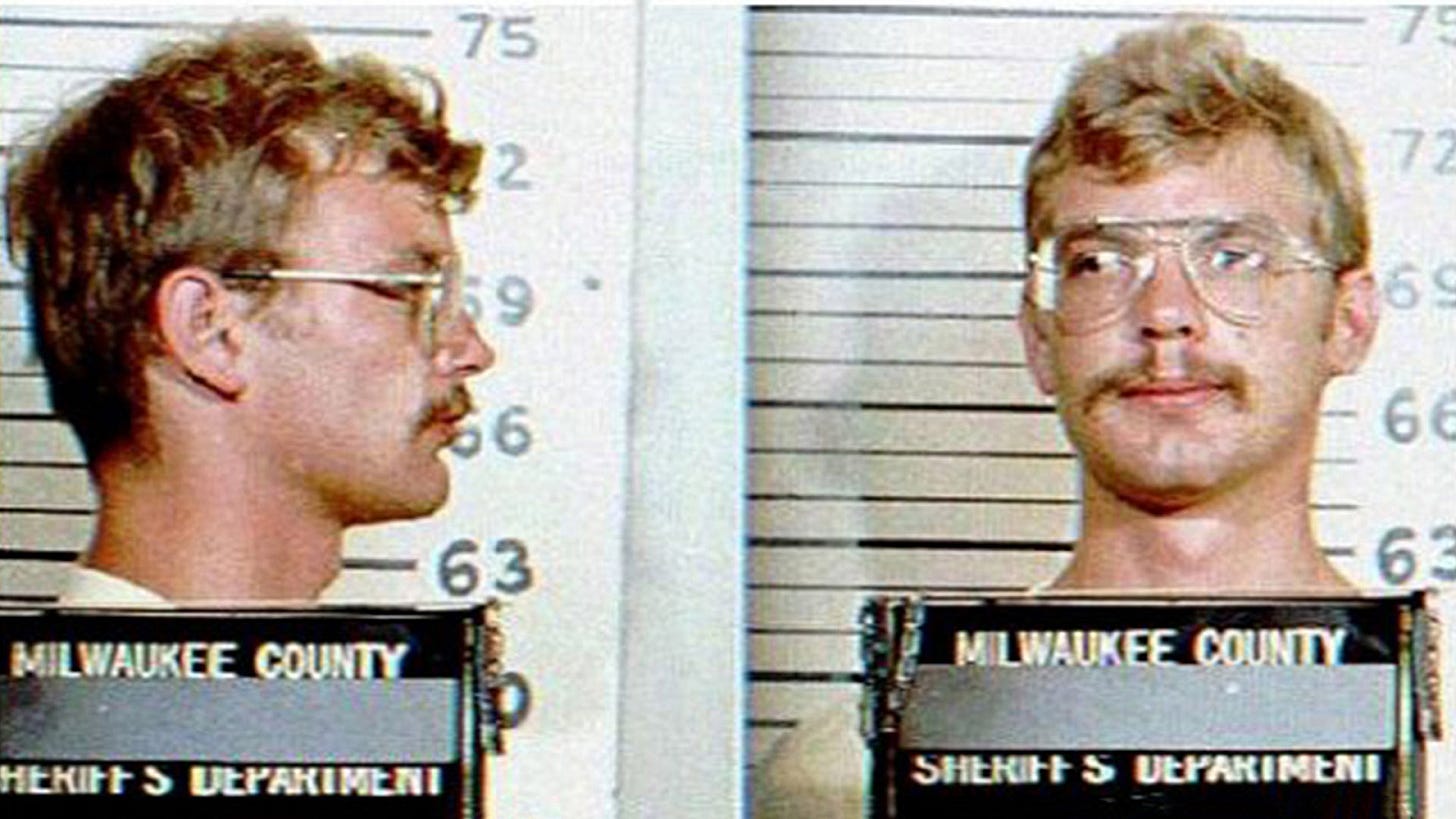

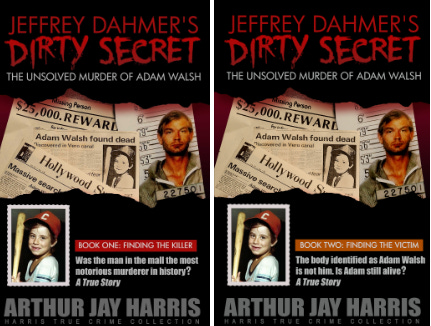

Darlene said she didn’t remember hiring Dahmer but wanted to see his photo before saying for sure. I sent her his 1982 black-and-white mugshot that Willis Morgan had seen in the Herald. (Here it is, in color, with his profile):

She still didn’t recognize him.

She said Sunshine was a small operation and its employees basically consisted of her, Tex, and her teenage daughter Denise. But she remembered the Walsh case very well.

Darlene’s fourth husband Glenn Hill had died three months before – and here I was, calling from out of the blue, from South Florida, reminding her of her life here twenty years before. As she became my most remarkable source, who opened up the Walsh story in directions I couldn’t have anticipated, I became her late-night, long-distance phone friend. She didn’t know Dahmer but she did know the world around Sunshine Sub.

In 1979, Darlene had managed an apartment building on 172nd Street, two blocks from the ocean, when at 34 years old she was diagnosed with a rare, fast-growing cancer. It was a complete surprise. Her doctor said she had maybe two weeks to live and wanted her to enter the hospital that afternoon. No, she said, first she had to order her affairs.

Foremost were her two teenage daughters. Their divorced father was mostly uninvolved with them, so legal guardianship would have gone to Darlene’s mother. Darlene did not want that.

From this extraordinary circumstance came an extraordinary solution. A tenant offered an idea: he knew a gay Canadian man who needed U.S. citizenship to stay in the country so he could keep running his restaurant. He would marry her, and upon her death, would assign guardianship of the girls as she wished, to her sister.

When I wrote my book I called him Larry, and the place he owned, on Collins Avenue, Beach Pizza. Neither are their right names, although the business was a pizzeria. You’ll see why I did that although I wasn’t asked to.

But if not for a murder, this marriage of convenience would not have happened. Did I need to remind you, this was Miami in the Seventies and Eighties?

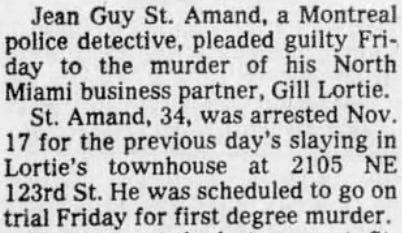

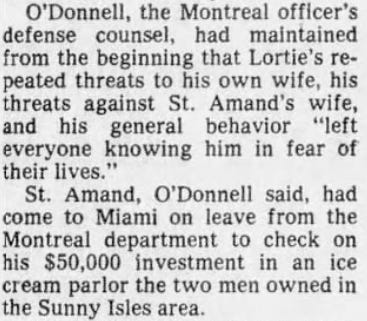

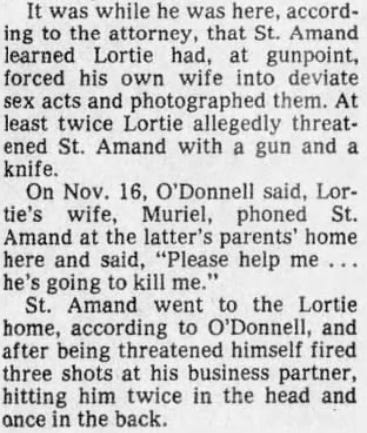

In November 1978, the original owner of Beach Pizza, which was also an ice cream parlor, was murdered in his North Miami townhome by a former Montreal Police officer.

Darlene told me that Gill had asked Jean Guy to buy a share of the business, and the sale had just been completed.

Muriel was glad that her husband was dead, Darlene told me. And I could not believe that I was detouring from my own story’s intricate soap opera to someone else’s. I thought of Dr. Seuss’s line, “Oh, the people you’ll meet!”

Jean Guy was able to plead down to manslaughter and was sentenced to eight years. As he was preparing to go to Florida state prison, in May 1979, he asked Larry, who’d been his supervisor at Montreal Police, to come to Miami to operate the place.

Back to Darlene: in June 1979, ten days after their introduction, she married Larry. The next day she entered the hospital. “I never, never expected to walk out of that hospital. Never, never, never. I’d said goodbye to my children.”

Three weeks and two major surgeries later she did leave, although they told her she had only another month. The doctors were right that it would kill her, but were off by approximately 11 months – and 41 years.

Next on The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 26: Darlene’s unlikely soap opera leads me, even more unlikely, to Jeffrey Dahmer.

You’re this far, you’ll want to keep reading, there’s so much more about this story you had no idea about. And we’ve just started Part 4, of 6 parts. FOLLOW, or SUBSCRIBE now for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. But if you’re the type who pays for subscriptions on Substack, maybe you might consider me too? (I wouldn’t mind in the least.)

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular, @investigative