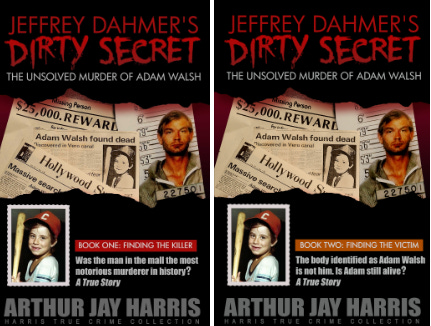

The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 41

Episode 41: The beautiful Bahamas – center of the Mob’s drug smuggling and money laundering

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Back once again to Allen Rivenbark:

He was part of a much larger federal criminal investigation called Operation Lone Star, which impaneled grand juries in Houston and Atlanta and involved drug smuggling and the laundering of billions of dollars from drug proceeds and illegal oil profiteering through tax attorneys in Miami. The laundering used offshore banks including in the Bahamas.

Organized crime members including Meyer Lansky and the Colombo crime family financed smuggling deals for five big South Florida drug rings, said a 1982 story in the Fort Lauderdale News. In October 1981, to the Houston grand jury, Rivenbark testified against Miami tax attorney Lance Eisenberg:

The skimmed casino money was Lansky’s, who the feds believed was also skimming from a casino in Freeport, Bahamas. From a 1976 story:

Lansky died in 1983. In 1984, Rivenbark, postmortem, was named as an unindicted co-conspirator in Lone Star as an associate of Lansky:

Chester grew up in Miami Springs, near Miami Airport, and was a pilot for Eastern Air Lines for twelve years until about 1978 when he took up smuggling, according to his October 1983 federal indictment in Lone Star, in Atlanta.

After his indictment, Chester tried to cooperate with investigators, but when that didn’t seem to work, in January 1984 he began speaking to the press:

Not surprisingly, U.S. government agents vigorously denied this.

Chester said drugs arrived by boat from Jamaica and Colombia to five “stepping stone” islands in the Bahamas, about 250 miles from Miami, which he bought in 1979. From those island hubs, the drugs left by plane to his ranches in Central Florida and North Georgia.

Big Darby Island has its own castle, built in 1938. In 2022, with the castle in need of repair, just this one island was for sale for $39 million.

Aside from whether Robert Vesco was working for the U.S. government while he was also a fugitive from justice, he’d been charged with looting $200 million from his investment fund and illegally contributing to Richard Nixon’s 1972 political campaign. Vesco was also close with Meyer Lansky.

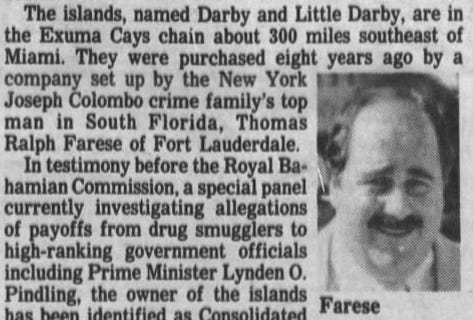

Another part-owner of the islands, said the Justice Department, was Thomas Farese.

The newspaper also reported that Vesco and Colombian drug lord Carlos Lehder had made monthly $100,000 payments to Pindling and others in the Bahamas to allow them to smuggle. The alleged bagman was a Nassau lawyer who had represented Chester.

After August 1980, when the Lone Star grand jury in Atlanta began investigating him, and then after Farese’s conviction months later, Chester apparently got more nervous about his smuggling business. In February 1981, he hired an accountant named Lesley Bickerton, whom he moved into his mansion in North Georgia where his wife and young daughter were also living, and who the Lone Star grand jury in June 1984 named as an unindicted co-conspirator. However, she testified against Chester at a pretrial hearing in August 1984:

Bickerton had first contacted prosecutors in Houston in January 1982 and gave them details of how Chester laundered his drug profits. Soon after, though, Chester’s attorneys contacted her. Houston-based federal prosecutor John Johnson testified:

Bickerton also testified that Chester told her about three men who’d cheated him and were killed. One, she said, was a potential snitch in his organization:

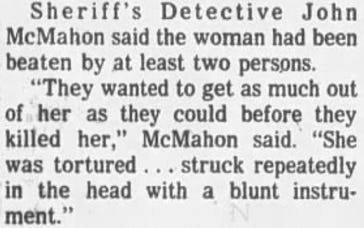

This, apparently, was one of those murders:

In 2023, a podcaster who interviewed Bickerton learned that the name of the private detective was actually Clay Williams. That Bickerton knew of the murder, which apparently happened in late September 1981, confirms her timeline of working with Chester.

Also in September 1981, on the fourteenth, the Broward Sheriff’s Office arrested 11 alleged mobsters whose voices they’d recorded after they’d gotten a court order to bug the Little Italy Restaurant in Hallandale, where they regularly met.

That same afternoon, they found one more mobster, at Fort Lauderdale airport. He was wrapped in a quilt, shot at least once in the back of his head.

Genco had been convicted in Ohio in 1970 of conspiracy to counterfeit a half-million dollars. At Lewisburg Federal Prison, he made a new friend – Jimmy Hoffa, and became his barber.

Actually, Bostick had been found in woods in Ohio on August 18, 1980, but his positive ID by a medical examiner made the news in Cleveland on September 16 – the same day Genco’s murder was reported.

Severed head and hands – was that a message, or done to prevent Bostick’s remains from being identified? It took a year to make the positive ID, and only after the medical examiner got chest X-rays from Bostick’s medical records and did a comparison. Was Genco about to testify to who had killed Bostick and other Cleveland mobsters?

Three months after Genco was found, sheriff’s deputies found another murder victim in the trunk of a car at Fort Lauderdale Airport – this time in the long-term lot.

Before 8 A.M. on December 7, 1981, three weeks after the Colorado plane crash and a month before Bickerton went to the feds, attendants stooped to pick up litter under the rear of a car that caught their attention: a stunning dark metallic blue ’76 Mercedes 450 SEL sedan. Then they saw blood red – a pool, dripping from the trunk. Thinking someone might be alive inside the trunk, they called for sheriff’s deputies, who crowbarred it open:

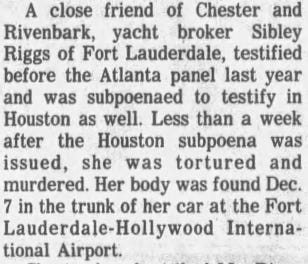

She was six feet tall, and underneath her was a bloody pile of papers and books. That day she was identified as Sibley Riggs, a Fort Lauderdale yacht broker, 43 years old.

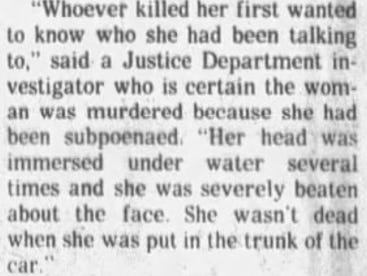

Dr. Ronald Wright, who did the autopsy on the child identified as Adam Walsh, did the autopsy on Riggs. He filed a report: she’d been repeatedly struck in the head with a blunt instrument, her lungs were filled with water, and she’d been strangled. Also, marks on her body showed that she’d fought back.

Police said she was last seen alive the afternoon before, and logs showed that the car had been in the parking spot for less than two hours. It was 1981, and the lot had no security cameras.

Lou Kilzer had told me that he’d been told John Monahan had identified her. Kilzer hadn’t confirmed it, but if so, it would have been Monahan’s third visit in four months to a morgue to identify bodies.

In 2024 I asked the Broward Medical Examiner’s office to see Riggs’s file, a public record. It didn’t mention Monahan, nor was there information of a visual ID by anyone.

It said she’d been identified by her vehicle registration record. I’m guessing the sheriff ran her license plate, it tracked to her, and as was reported, there was no record of the car being stolen. If her driver’s license was still on her person, that would have substantiated it, although in 1981 Florida licenses didn’t have photos.

But isn’t that just a presumptive ID, like we’ve been through before? A visual ID would have sealed it.

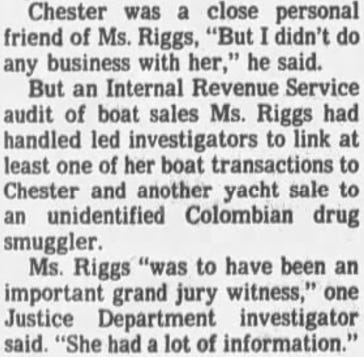

Riggs was Allen Rivenbark’s girlfriend:

Going back to my lunch in May 2014 with private investigator Steve Votra, which was just after I’d spoken with Lou Kilzer, I’d asked him about Riggs. In my notes I have just this line:

Monahan had a “history of fucking her brains out.” But I hadn’t published or shared that until now.

That made two girlfriends Monahan lost within three weeks.

For a year police had no substantial leads, then in November 1982 the Fort Lauderdale News reported what unnamed federal authorities had told them:

That last bit about her being alive when she was placed in the trunk wasn’t in the Medical Examiner’s file.

So circa 1981, the IRS was looking at salespeople of boats. Riggs worked for the Bertram Yacht Company, in Miami, which did not manufacture yachts but sold them, shall we say, pre-owned.

This ties in with another book I wrote, about the murder of Cigarette powerboat builder and champion racer Don Aronow, in 1987. In the Sixties, Aronow and Bertram had been rivals in Miami in building, racing, and selling smaller “go-fast” boats. Bertram had been the first to market a revolutionary hull design that was stable in rough water; his boat demolished previous racing records.

Over the years, Aronow improved on Bertram’s design, added severely overpowered engines, and eventually overtook Bertram in races, sales, and publicity. Because his boats were much faster than anything marine patrols had, dope smugglers saw an opportunity. They used them to meet “mother ships” offshore to pick up drugs, then carry them the so-called last mile to the U.S. coast – often Florida.

By the Seventies, Bertram had decided to get out of that business, possibly because he realized who much of the clientele had become. Aronow, an associate of Meyer Lansky, had gotten out after Bertram did yet still stayed connected, and at least in 1986 had the IRS looking at him. To smugglers, Aronow generally (if not always) had sold his boats cash-and-carry.

Referring to Riggs,

Rivenbark, another Lansky associate, was allegedly involved in money laundering. Had he bought his yacht using cash? Had Riggs been part of laundering that money? Had he used the yacht for pleasure boating, or had he cleared out passenger space to hold cargo?

Then there’s the issue of cooperation with the IRS when they’ve launched what apparently was a criminal investigation of you. Here’s your no-bueno choice: Don’t cooperate, and risk getting charged in a criminal conspiracy. Cooperate, and risk facing down the barrel of a gun. This was apparently Aronow’s choice at the end of 1986, with even a few more complications, like his publicized friendship with the then-Vice President, George Bush.

Don’s end was similar in that he, too, was killed in his Mercedes, in February 1987. He was shot by a man in a passing Lincoln Town Car, who fishtailed and got away. The same hitman had previously killed Tommy Felts, one of Gil Fernandez’s gym rats, who’d killed a smuggling associate of one of Aronow’s friends.

How’s that for interconnectivity?

More than forty years after Riggs’s murder, the case remains unsolved.

Funny thing – during one of my visits to the Broward Medical Examiner’s office to see Riggs’s file, the records clerk told me that a Broward Sheriff’s cold case detective had just asked for the file, too. That was Det. Andrew Gianino, and in February 2025 I met with him at the sheriff’s homicide bureau, in Fort Lauderdale.

I shared a lot of information about the case I’d gathered that he didn’t have, but what I wanted from him was whether Monahan had visually identified Riggs.

He said Dr. Wright, since his ouster as Broward’s chief medical examiner, had not been cooperative on old cases with the BSO, either. I told him there was no autopsy report in the Adam Walsh file.

He went, What?

I was right that Monahan’s name isn’t in Riggs’s M.E. file, he said, but the BSO file did, in fact, have a document showing that Monahan did visually ID her. He needed permission from a supervisor to release it to me, which he thought he could get in a week or so.

Wait – let me stop. Wow.

Gianino agreed that Riggs’s murder was a hired hit. In whose benefit was it? Chester was an obvious person to consider; after Rivenbark’s death, he’d taken his position in the smuggling ring.

Gianino didn’t know much about Monahan, hadn’t ever seen a picture of him (I showed him one), nor what Steve Votra had told me about Monahan’s relationship with her as well as Monahan’s relationship with Rivenbark.

Riggs had testified to a grand jury. Was she cooperating? Might Monahan also have been been asked to testify? After Riggs was killed, was Monahan a potential next target?

On two crucial occasions, Monahan did not travel alone. Hollywood Lieutenant Hynds told me that he and Monahan had gone together to the Vero Beach morgue for Adam’s identification. They’d driven at a high speed, not in a police car but in Monahan’s Mercedes, driven by his chauffeur. Jay Grelen had written in his stories for the Mobile Press Register that the Eagle County sheriff’s chief investigator said that Monahan was accompanied by his “gorilla.” Steve Votra saw Monahan’s “gorilla” at Herby Meier’s funeral, if not also at the Eagle County morgue.

Gianino said he had a friend within the Department of Justice who might be able to find old documents of what Riggs might have told an assistant U.S. Attorney to prompt her subpoenas. Meanwhile, as to the hitman, a DNA test from biologic material apparently taken from the crime scene – it seemed obvious that’s from where it came but he said he couldn’t say – had just come back with a partial reading. Maybe in the fight she scratched the guy, or guys, and it came from under her fingernails. It wasn’t good enough to put into the federal CODIS database, he said, but was good enough to try to match one-to-one with a single suspect. That would take some guesswork.

I would have to wait to see how much Gianino could tell me from what was in the file.

Months later, I hadn’t heard back, and he wasn’t responding to my messages.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 42: The Bahamas – More Miami than Miami?