The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 39

Episode 39: Where the police knew that John Walsh used to eat stone crabs for lunch

Link to Episode 38: “Adam Walsh: Myth and Mystery”

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Frustrated by Hollywood Police’s denial of his request to open its Adam Walsh case file in 1995, Jay Grelen ran up his editor’s tab even more. Weeks after his series ran, his newspaper sued the police under Florida’s public records statutes. Quickly, three local South Florida newspapers joined them.

Under Florida law, local police cases become public, on request, once a case is closed by arrest, or dormancy. Cases are considered “active,” and therefore exempt from public disclosure, only if police have a “reasonable, good faith anticipation” they will secure an arrest or prosecution “in the foreseeable future.”

The Walsh case was fourteen years old without an arrest. Hollywood Police said they were still working the case but that wasn’t the legal standard. It was whether they had a reasonable, good faith anticipation of an arrest or prosecution in the foreseeable future.

In October 1995, a Broward County judge gave police six more months to make an arrest, if possible, but said that if they couldn’t, or the State Attorney didn’t bring the case to a grand jury, the public records law would force him to order the file open.

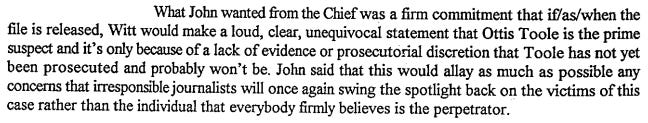

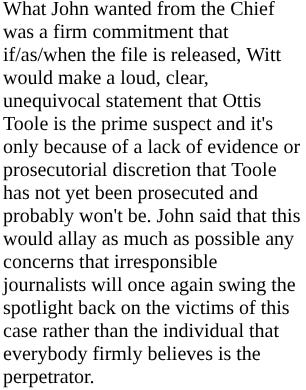

The Walshes joined the police and State Attorney in their opposition. As the February 1996 court date got closer, on January 16 John Walsh and his counsel got an appointment with Hollywood Police Chief Richard Witt. The meeting didn’t go as they’d hoped. Walsh’s attorney shared this memo, dated the next day, with their friends at the Broward State Attorney’s Office:

Toole, the suspect who “everybody firmly believes is the perpetrator,” notwithstanding, of course, the “lack of evidence.” And darn those “irresponsible journalists” who might point that out.

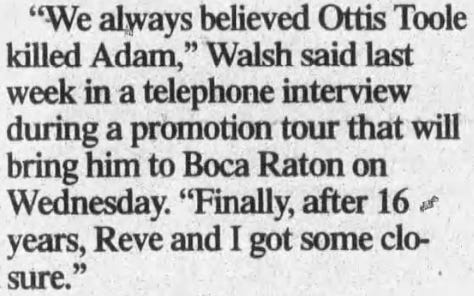

Walsh’s statement, or sentiment, wasn’t made public when it was written. It was also striking that he thought that Toole had killed Adam, even before the case file was released. He said as much the next year when he toured to promote his book Tears of Rage:

Always believed? It’s not what he said as late as 1994:

Toole was in prison in 1994.

In February 1996, with the judge’s deadline approaching, Walsh sent this written statement to The Miami Herald:

Was Walsh upset that the press would be able to read into the police’s investigation of Jimmy Campbell? Was that some of what he was talking about when he said that “irresponsible journalists will once again swing the spotlight back on the victims of this case”?

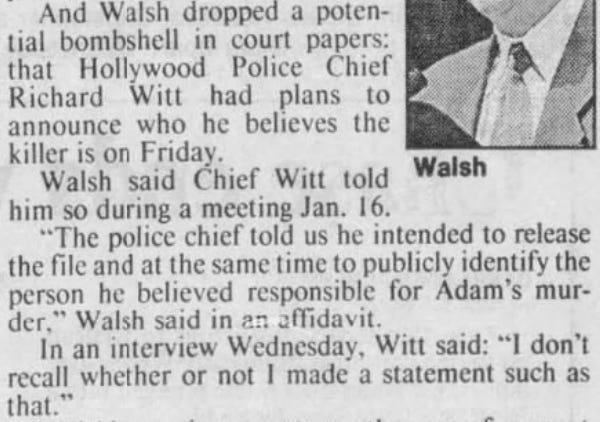

Besides, had Chief Witt said what Walsh said he said?

On February 14, Walsh filed an affidavit to the court:

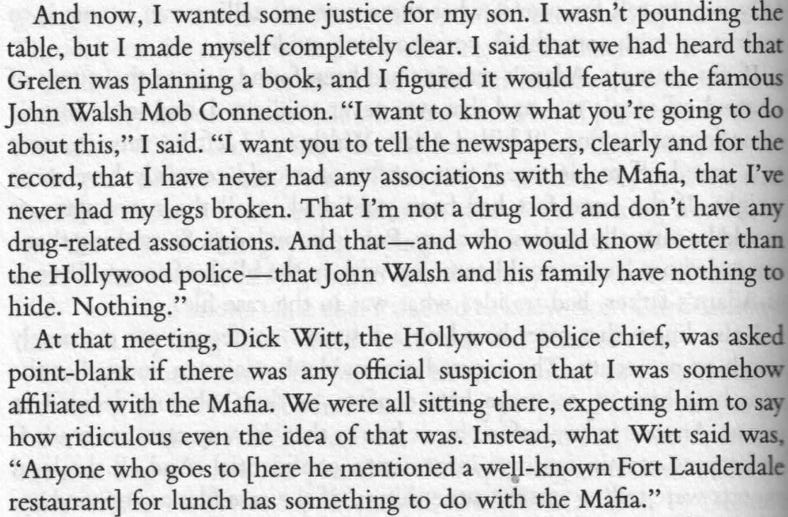

In his book, Walsh wrote about that January meeting with Chief Witt:

Walsh’s investigator, retired Miami Beach Police sergeant Joe Matthews, was also present at the meeting and wrote about it in a book he co-authored with Les Standiford in 2011. Matthews confirmed that Walsh did “frequent” the restaurant that Witt mentioned:

What was the name of that restaurant? Why didn’t Walsh or Matthews publish it?

Had they, most everyone in South Florida would have recognized it:

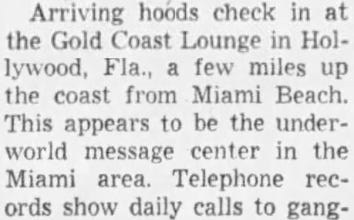

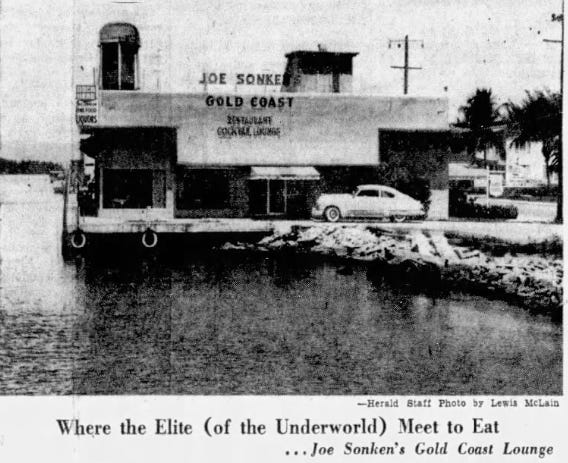

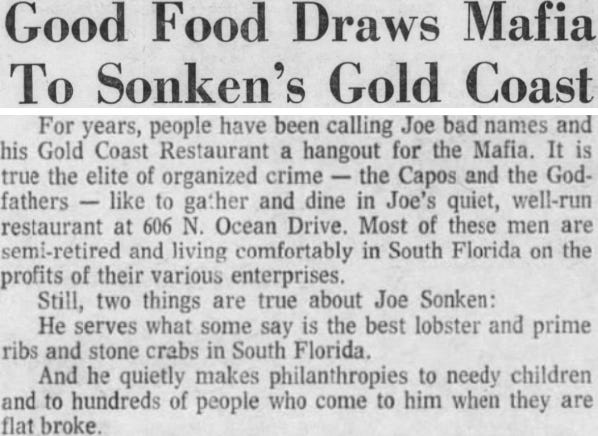

The likely place wasn’t in Fort Lauderdale proper, it was on Hollywood Beach on the Intracoastal Waterway side of A1A, the ocean road, just north of Hollywood Boulevard, and had dockage space. It was called Joe Sonken’s Gold Coast Restaurant, and its public notoriety went back at least to 1957, when Washington syndicated newspaper columnist Jack Anderson, investigating the mob in Miami, wrote this, reprinted in the Herald:

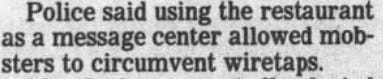

A much later story explained:

By 1971, the description of Sonken’s belly hadn’t changed, but what had looked like a dive from the outside had since gotten “plush.”

In 1978, when I moved from Baltimore to Hollywood (to work for the Sun-Tattler, my first staff job in newspapering), I first lived on Hollywood Beach, up the street (to the right, in the picture) maybe ten short blocks from Sonken’s. This is how it looked, around then:

Ever stumble into a motorcycle bar, uninvited? Unless you parked your motorcycle in front? Writing this years later, outside Sonken’s, I perceived, you didn’t need to park your cycle, you needed to valet your Caddy. Entry was nearly as intimidating to me, and I’d never considered venturing inside, even to look.

Okay, I blew it. I should have at least walked in.

Just steps to the right in the picture, however, were two very cool, divey places that had covered open-air dining or drinking, also right on the Intracoastal. They were our favorite places, and we went to them a lot. So we didn’t need Sonken’s.

Anybody, of course, could go to Sonken’s, but if you did, you knew where you were, especially if you “frequented” the place. It was actually one of its appeals, and Sonken never hid from it. Nor did the mob guys.

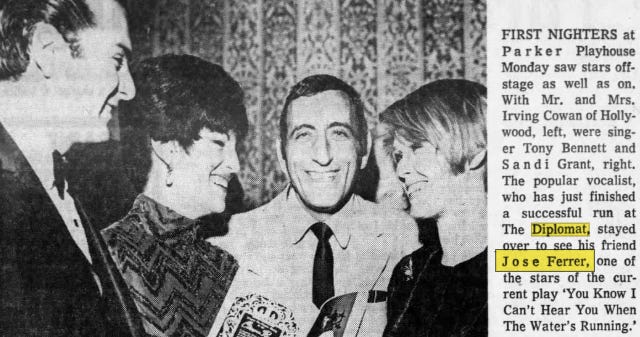

Other regulars at Sonken’s were entertainment people, when they were in town:

Know who else was probably at that late supper?

The owners of The Diplomat Hotel – and Tony Bennett, who had just played there for a week and wanted to see Jose Ferrer perform in Fort Lauderdale:

The food apparently was good:

Here’s some of the Lansky connection, as reported by Hank Messick, who investigated the mob in South Florida for The Miami Herald:

Reflecting what Chief Witt told John Walsh, law enforcement perennially kept the Gold Coast Restaurant under watch. This was in Sonken’s obit:

From another obit:

This is from Freedom of Information Act materials from the FBI, which became available after Sonken’s death:

These were some of law enforcement’s failed attempts:

Sonken’s denials were apparently good enough for the Hollywood Police. Two months before his crime-investigation committee appearance, a group of Hollywood cops held a stag party – at the Gold Coast.

Yeah, somebody leaked that – doesn’t say who.

Afterwards, did anyone at Hollywood Police take any shit for that?

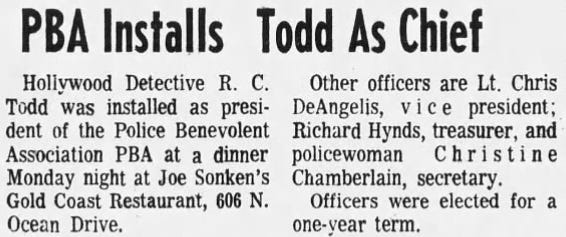

Two years later, this:

A name on that list stands out: Richard Hynds, who as a lieutenant eleven years later was in charge of the Adam Walsh case and went with Monahan to the Vero Beach morgue. And two years later let Walsh’s attorney, suing Sears, see some of the police case file.

Then again, even Jack Anderson was seen at the Gold Coast, a decade after he wrote his 1957 column:

Maybe Sonken leaked that to the Herald – and got a big laugh from it? Maybe Sonken came to the Cowans’ table, and they introduced Anderson to him?

In 1982, it was Hynds who the Herald’s Tropic Magazine quoted about Walsh’s rumored connections to the Mob:

Was that last line a Freudian slip or a double entendre? Did anyone at the time notice? Police divers had searched the canal’s murky bottom for the rest of the child’s body but never found it. Here, Hynds said there were no skeletons in the Walshes’ closet.

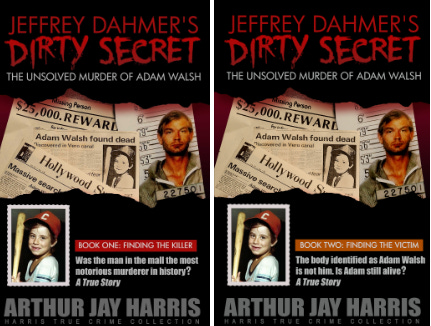

Ten years later, the apartment of a suspect had literal skeletons in his closet. Severed heads, too.

Yet the Walshes most certainly did have skeletons in their closet, just not literally. When Hynds said that to the Herald, he knew very well that both Reve and John had confessed to having affairs. It was one thing not to say that for print, and another to assert that they were pristine.

But the other rumors in print I found that John might have been Mob-connected were there because Walsh himself had raised them. The first one was six months after the Tropic story, to an Associated Press reporter:

What?

Then a year later, when John Walsh called a press conference after the police said Toole had confessed, he blasted the Miami Herald:

Geez, the Tropic reporters had only quoted the cops on the case.

Similarly, Joe Matthews could have left this out of his book, but didn’t:

Um, okay, it’s a rumor — but somebody kidnapped your child from a store and chopped off his head because you wouldn’t participate in a drug deal?

Were people here being forced, not just by threat but by actionable murder, to take part in drug deals when they’d never handled drugs before?

The kind of thing that brought enforcers like Big Jim Capotorto to ring your doorbell late at night were past due drug debts. Like manufacturing businesses that allow retailers terms of 30, 60, or 90 days, the drug business was generally a consignment business; the growers, processors, packers, shippers, receivers, distributors, street dealers and every other sort of middleman who handled the drugs mostly got paid after retail consumers bought them. Most everybody owed most everybody up the line.

Manufacturing televisions or growing wheat uses established channels to ensure that everybody eventually gets paid. But in the higher-risk, higher-markup, not to mention illegal, drug business, if somebody within that line disappeared or didn’t pay, or their drugs were stolen or lost at sea or the police seized them, then everybody else was stuck-o. And for them the justice system was the Big Jims of the world, who were sent out to make the responsible party make good, with pain no issue.

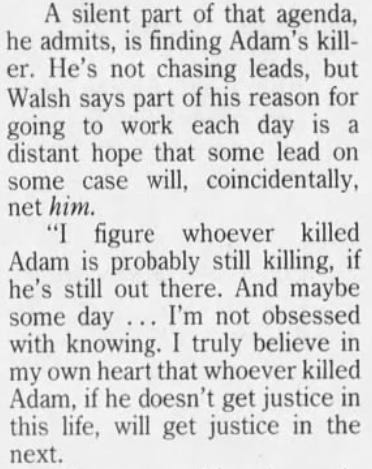

But did those guys kidnap children? 1981 in Dade and Broward counties was the worst year on record for murders, inflated by drug-related killings. There were kidnappings, yet no one had heard of one against a trafficker’s young child. And a beheading sounded more like the work of a psychopath who just liked doing that stuff, not a lovable, huggable guy like Big Jim, who swaddled babies.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 40: The Mob wars in Broward in 1981

This rabbit hole just gets deeper, Art! Some very dubious connections to the Walshes there!