The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 31

Episode 31: The dead guy behind the dumpster

Link to Episode 30: Breaking the Dahmer-Adam story.

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Unlike the other important witnesses I’d found, I hadn’t been able to spend unrushed time talking to Ken Haupert Sr. When I tried to reach him in 2007, I found he’d since closed his Oklahoma sub shop and his home phone number wasn’t working. To find him, I used the water department records at Dewey city hall, again. When he answered the phone, he was just as surprised at how I’d found him as the first time. He was opening a new restaurant across the Kansas border in Caney, not far from his home.

He’d seen what Willis Morgan had said about how Dahmer had looked at him. “That could only have been Dahmer,” he said. “The way Dahmer looked at people he disliked, you wouldn’t know it unless you saw it. There’s not another person in the world who had that look.”

He recalled again the moment Dahmer had given him a similar look. Haupert had told him, “You ever look at me like that again, you’re in big trouble.”

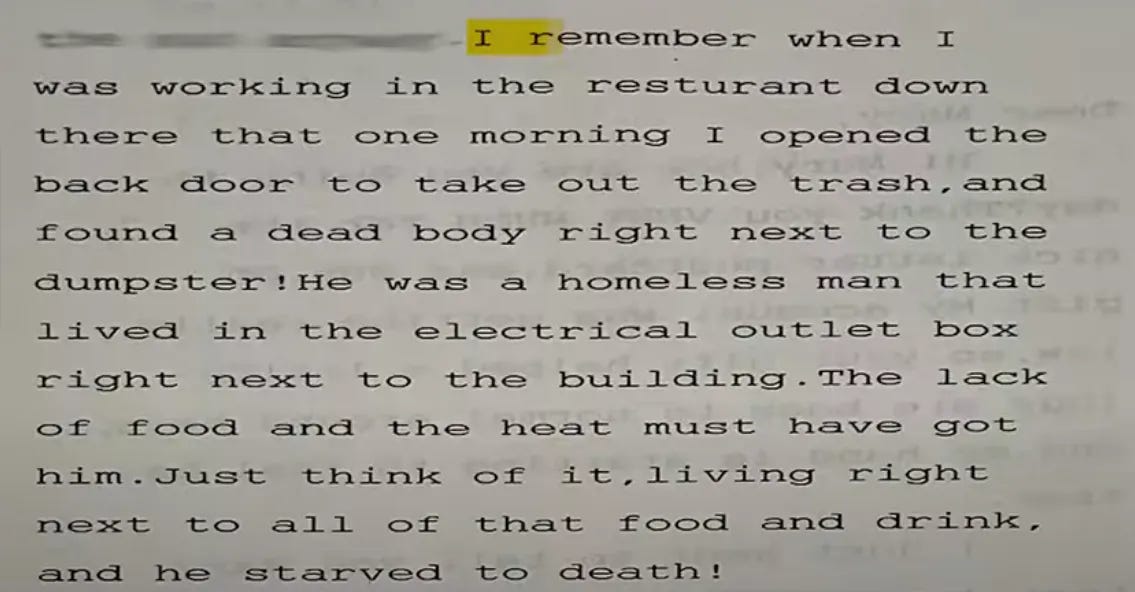

He also remembered something he hadn’t thought of before. A week or two after he hired Dahmer, Jeff told him there was a dead man behind the dumpster. He said he’d been stepping over him for two or three days.

“Why didn’t you say something to me?” Haupert asked him, sounding exasperated to me. “Maybe he needed help, maybe he was still alive.”

Haupert said he rushed out and saw the body, which had turned blue and had flies. He called the police. He thought the man was about 50, sickly, and didn’t look like he’d been beaten. Haupert guessed he’d been eating out of the dumpster – as he’d seen Dahmer doing before he hired him.

The police had made a report, he said. He didn’t have it or know the date, but the address must have been the store’s, 17040 Collins Avenue.

I called Miami-Dade Police Central Records. They had 1981 police reports on microfilm but they weren’t computerized. Without a victim’s name I needed a case number to find it.

This would have been another dead end, except I knew that the Miami-Dade Medical Examiner must have received the body, and they’d kept their records going back to 1956. Even if 1981 wasn’t computerized there either, a hand search there wouldn’t be as daunting. I asked a clerk there to look through their deaths in June and July 1981 for a body found at that address.

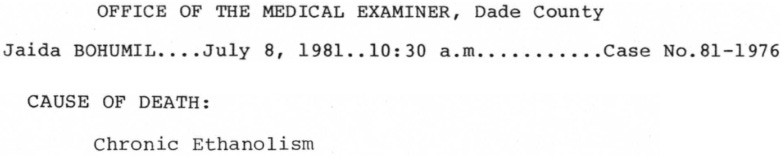

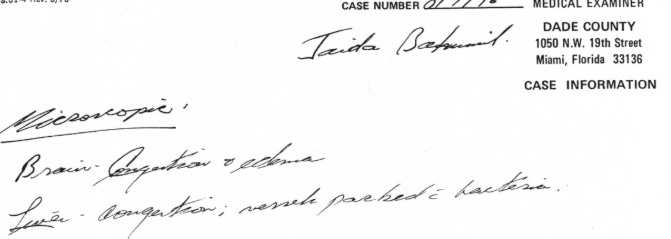

Days later, she had it. The M.E. had his name as Jaida Bohumil, age 55. Police had identified him by his fingerprints – in 1971 he was picked up in Dade County for vagrancy and drunkenness.

The police report date was July 7, 1981 – 20 days before Adam disappeared.

The medical examiner had the police case number. I ordered it from Miami-Dade Police, as well as the autopsy report and case file from the M.E.

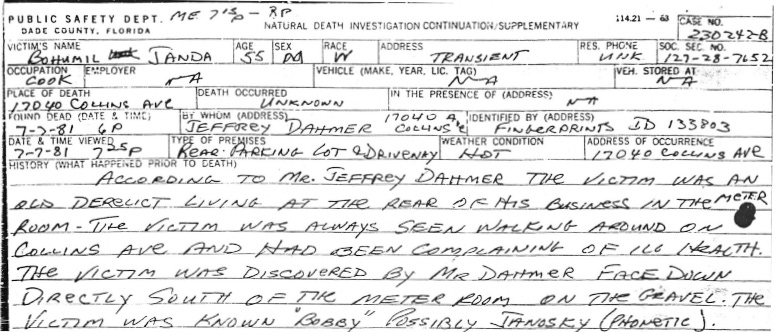

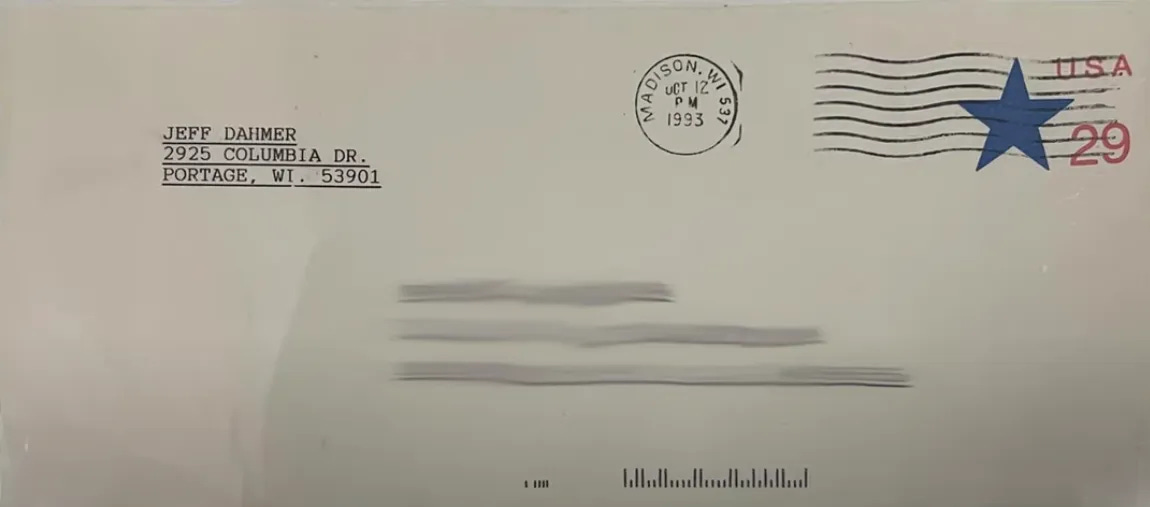

When I got the police report, the reporter of the crime was “Dahmer, Jeffrey.” His address and contact phone were the same as for Sunshine Sub.

Finally, here was certain evidence, which Hollywood Police had tried to find but didn’t, that Dahmer had been in Miami.

The report was three pages, its supplement written by a homicide detective:

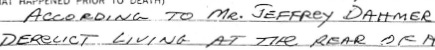

In fact, all the information taken at the scene was “According to Mr. Jeffrey Dahmer.”

Dahmer clearly knew the deceased:

On his rap sheet, all for minor infractions, two of his arrests were as Robert Janda. Another, which sounded closer to his given name, was as Bohumil Vaclau Janda.

The police report form used was for natural death investigations. The body had no bleeding or obvious marks of violence other than scratches likely from gravel. He was found cold, and was wearing only one tennis shoe – the detective found his other shoe in the mall’s electric meter room, about 20 feet away. His last known address was from 1970, and police had found no kin to notify.

In movie Westerns, it was honorable to die with your boots on. This man had died with his boot on.

What was that about? Had he wandered out of the meter room wearing one shoe, and gotten only as far as the dumpster? Or had he died in the meter room after a struggle and was put behind the dumpster? Was his body intended to be lifted into the dumpster?

Haupert told me he knew that the man had been living in the meter room – “It smelled, so you didn’t go in there.

“He ate from my dumpster. Sometimes I put good stuff in it, and it would be gone.”

Geoff Martz from ABC asked Lionel Dahmer if his son had ever told him about finding a dead body in Miami, or the meter room. He said no. He also said Jeff had never mentioned Adam Walsh, nor had Lionel asked him.

“I think he was totally honest,” Lionel said, although he also thought Jeff was capable of lying.

Geoff also asked if he’d told John Walsh that his son might have killed Walsh’s son. He seemed totally surprised at the reference, Geoff told me. Lionel said that when the Milwaukee station had asked him that, he’d told them No comment.

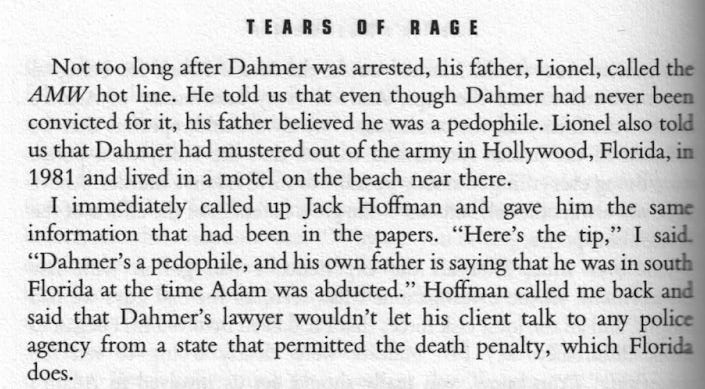

This is what John Walsh had written in his book ten years earlier:

And then, to Geoff, Lionel suggested that I was just trying to sell a book.

Billy Capshaw told me that Dahmer had never mentioned his mother and told him that he had no siblings – although Jeff had a younger brother. But he did speak about his father. He told Billy that he wanted to please his father although he hated him. In Jeff’s early years, his father had tried to teach him anatomy, which Billy said may have explained why Jeff knew how to pronounce anatomical Latin words.

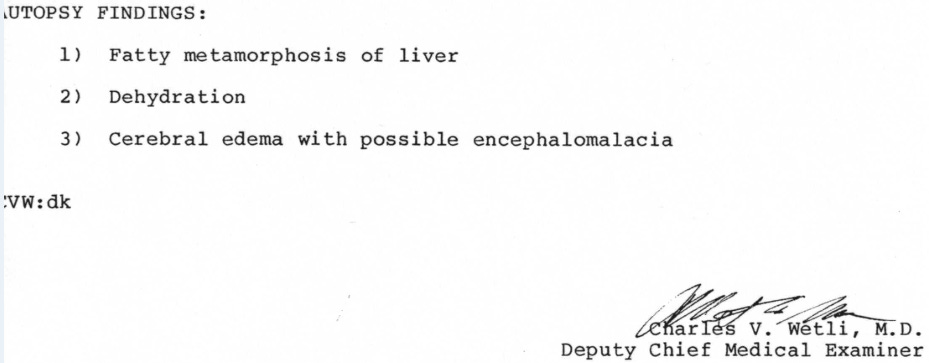

The report of Janda’s autopsy, done the next day, said he was 5’4” and 78 pounds. His stomach had less than a half-ounce of fluid – he must have been hungry. Deputy Chief Medical Examiner Charles Wetli wrote that his probable manner of death was natural, caused by chronic ethanolism:

Both ethanolism and fatty metamorphosis of liver suggested alcoholism. Encephalomalacia is the softening of brain tissue after either a stroke in the brain, an infection, or trauma to the cranium.

That is, he could have been struck in the head.

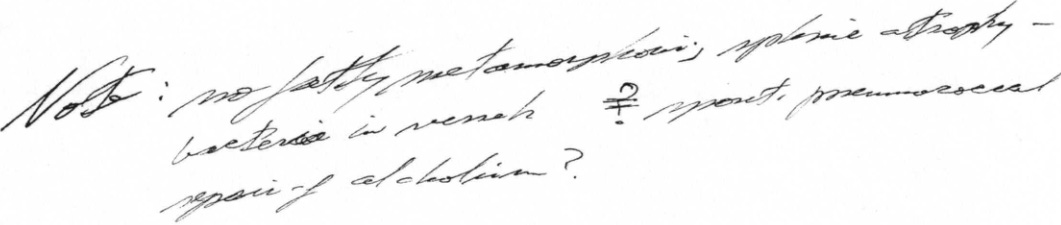

But in a note for the file dated six days later, after viewing microscopic slides, Wetli handwrote, intriguingly, “Note: no fatty metamorphosis.”

He didn’t revisit his opinion of manner or cause of death. But if he hadn’t died of alcoholism, had he died from a head injury?

And how suspicious was it that Jeffrey Dahmer said he discovered a dead body? Milwaukee detectives had asked him early on to recount all of his interactions with police during his lifetime. He didn’t mention this.

Did he forget? Would you forget finding a dead human body? Ken Haupert hadn’t. Do you think the men who found the child’s severed head in the canal, floating, casually ever forgot that?

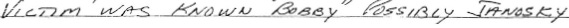

No one in the larger Dahmer case seemed to have heard about this. Nor had Dahmer told Jack Hoffman when he’d interviewed him about when he was in South Florida in 1981.

Almost all of the homicide detectives and psychiatrists, who presumably had seen it all, believed Dahmer when he said he’d admitted all his murders. But now let me ask some real experts – you:

Who’s the last kind of person in the world whose word you should take when he says he’s telling you the whole truth?

Okay, a lot of kinds of people would be tied for last. Your husband. Your wife. Your kids, your boss. But at least on the list, would one of them be a caught serial killer?

I think the detectives and doctors believed him, maybe because they hadn’t caught him in a lie.

In 2022, a cartoonist in Paris, Yacine Elghorri, caught him in a lie.

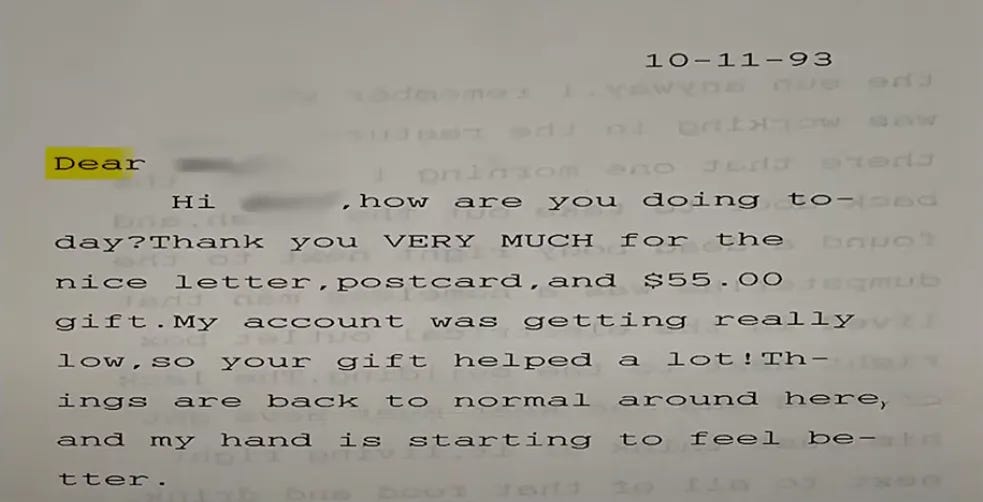

Jeffrey Dahmer had remembered the incident.

Yacine and I had spoken prior to this. On a serial killer memorabilia site, he found for sale a letter that Dahmer had written in 1993 to a pen pal while in state prison. He sent me screenshots. The name of the letter’s recipient had been removed in the online posting:

The date was a little more than a year after Jack Hoffman and Dan Craft spoke to him, in the same prison, in Portage, Wisconsin. Had Dahmer mentioned it, I’m sure Hoffman would have asked him if anyone had reported it to the police, and therefore there would be a report. Maybe Hoffman, who’d worked as a cop in Dade County, would have thought like I did to go to the medical examiner’s office in Miami to have them search for the autopsy report.

Maybe Dahmer didn’t tell them because he killed Bobby Janda and thought that in Florida he could get the death penalty for it. Many people were disappointed that Dahmer hadn’t gotten death for so many other murders, but Wisconsin didn’t have a death penalty.

Or maybe – with some further sleuthing, what I first found and pursued in 2002, Hoffman would have pursued in 1992.

And Dahmer, then still alive, might have faced the death penalty for killing Adam Walsh.

Back to 2007: After the incident, Haupert told me, he realized that Dahmer didn’t seem to have anywhere to live – which would have been consistent with Dahmer giving his address as Sunshine Sub. Of course, it might have been in the back of Haupert’s mind because he’d hired him after the second time he saw him look for food in the store’s dumpster.

Within the next week or two, Haupert said he’d arranged for Dahmer an inexpensive room at the Bimini Bay, which rented by the month or week. He advanced the money needed to get him in, which Haupert also recovered later from his salary.

Billy Capshaw believed that Jeff had lied about killing only 17. When I told him about this, he thought Jeff likely had murdered the man. He said Jeff knew how to suffocate someone without leaving a trace. It was simple – he’d sit on the person’s chest or upper back until he stopped breathing. Jeff had done it to him, and Billy had learned to breathe shallowly and not seem bothered, otherwise Jeff would clobber his fingertips with an iron bedpost. That the homeless man was so small made it easy for Jeff, who was very strong. Haupert had made the same point about Dahmer’s strength, especially in his hands. He’d seen it when he scooped ice cream.

I was sharing a lot of information then with Willis Morgan, who made the next connection: What if Dahmer killed the homeless man so he could sleep in his room? And then he made an even larger leap – what if Dahmer used that room 20 days later to keep, kill, or disembody Adam?

Gulp.

From the police report description, Willis found the room, in the rear alleyway of the 170th Street Shopping Center. It was at the end of a low trafficked gravel-floored hall, underneath exterior stairs leading to the second floor, steps from a large dumpster and a back door marked 17040. On the room’s brown painted door, some of its wooden jalousie slots busted out and rotting, was a red posted sign:

It was unlocked, and he went in.

I told Geoff Martz the theory. He thought that the room needed to be checked out.

Another ABC producer, Shana Hildebrand, asked the shopping center manager for permission to let us search. Finally he consented, but only if we worked in the middle of the night, so as not to attract attention or distract from business.

We needed a crime scene professional. My first thought was to call what was then called Metro-Dade Police, which did detective work for the small City of Sunny Isles Beach Police Department. I had long since faxed the Dahmer police report to Chuck Morton, with a brief explanation and an invitation to call me, not that I was surprised when I didn’t hear back. So Geoff and I agreed not to call the Broward state attorney or Hollywood Police, who we expected would dismiss us.

I asked my friend Bob Foley, a retired Broward Sheriff’s crime scene detective, now in Cape Cod, and he suggested we hire someone privately but not from South Florida because the crime scene people here all knew one another. On the advice of one of Martz’s contacts he found Jan Johnson, a criminologist recently retired from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. She lived upstate, in Pensacola.

I didn’t see the room until the day before we went in. Immediately behind the door was a group of electrical boxes. The room turned to the left and extended about 30 feet by 10 feet. Despite the sign on the door, it was impenetrably filled with junk – old pipe, a toilet, bricks, a shopping cart, plastic milk crates full of miscellaneous hardware, and a wheelbarrow. The floor was cement, and a single light bulb shone from the ceiling at least 12 feet above. It also had a large sink and running water.

I got a feeling: wild goose chase.

Geoff reassured me, yes, it probably was, but still, here was a space that Dahmer had likely controlled. If nothing else, as a visual it was a winner. The two other places where there was a possible trace of Adam weren’t available: the Bimini Bay motel had been leveled, and for all I’d tried I could never locate the blue van, which after 26 years was likely no longer on the road. This newly discovered meter room was the only place left where Dahmer might have had some privacy.

Besides, as Willis suggested, it made more sense than his hotel room. It didn’t have his name on it (except for that totally obscure police report), so he wouldn’t have had to be meticulous about cleaning up. I added that Dahmer liked to take his time cutting his bodies, he seemed exacting, and he probably would have taken it somewhere rather than do it in the pizza van.

With Jan, ABC’s two producers and a camera crew, we got to the meter room after 4 A.M. on May 24. We schlepped out most of the junk inside it while anticipating some inquiring patrolman who never showed.

The concrete walls and floor now bare, we all scanned for stains that might have been blood. If there was anything in the room, I thought, it would be in one of the two furthest corners from the entrance. Leaning on the wall between those corners was an old, rusty, waist-high lumberman’s ax with a wooden handle. No, couldn’t be, I thought. Next to it, was an equally old sledgehammer.

Jan marked interesting stains on the walls with stickers printed with arrows. But it wasn’t until she pulled out colored-glass goggles for us all, and aimed a colored light on one of those corners, that a pattern opened up to our eyes. On the southern wall, almost at the southwestern corner, now strikingly obvious, was a rain of stains, maybe a hundred droplets, starting about a foot above the floor to above where we could reach:

When Jan turned off the light and we safely removed our goggles, it was no less obvious:

The rain of stains was in two directions, she showed us. Assuming a chopping motion down, the cast-off droplet stains rose, climbing the wall. As the chopping instrument was pulled back, other droplets were cast off in a downward direction, the reverse. There were less of those. Looking at the scene clinically, I thought it was spectacular. Jan agreed. While the camera rolled, I asked her if it looked like it might have been related to a homicide. It did. I later learned that one of her expertises was in crime scene blood pattern analysis.

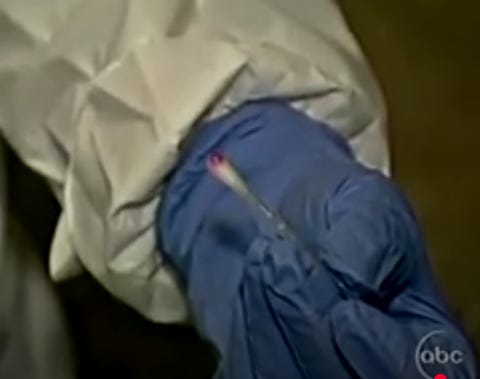

But was this blood? Using a swab kit, first she showed us what a positive result would look like, using a control. She soaked a swab with distilled water, placed a drop from a vial she’d brought containing horse blood, then doused it with phenolphthalein. The swab turned magenta – to my eyes, the whole swab burst with blood color.

Next she did a negative control. She dabbed another water-soaked swab on a spot on the wall about ten feet from the spatter corner, hoping for transfer, then added the chemicals. Concrete, she said, is one of the toughest surfaces to get transfer from. The swab didn’t turn color at all.

Then she took a sample from a spot on the wall in the corner and added the chemical. The swab reacted just as it did in her control test. It turned magenta.

I shivered. In an obscure room that connected to Jeffrey Dahmer, paces away from where he was employed that summer of 1981, was a large pattern of spatter, possibly indicative of a homicide, which tested positive for blood.

Was this Adam Walsh’s blood?

Unfortunately, this was the peak moment. Perhaps showing us the limitations of crime scene forensic science, nothing else got us further. After taking two more phenolphthalein samples that indicated blood – then one that didn’t – Jan tried a field test called Hexagon OBTI, a sort of litmus paper that can determine whether blood is human or not. The emergence of one band on the paper would indicate negative but that the test is working, two bands positive, that the blood is human. She showed us, the horse blood resulted in one band.

And so did our sample, twice.

We were left to wonder whether we’d just proved the blood was animal and not human, or merely gotten an inconclusive result, as Jan suggested. The field test shouldn’t be relied upon, she said.

By now the business day had begun and our time was up, as the shopping center people informed us in pretty certain terms. We’d made a mistake by not starting earlier. To earn time for Jan to gather more samples that she could submit to a crime laboratory, outside I song-and-danced the maintenance men, regaling them with the story of what the hell we were doing here, what infamous killer we could prove had trod these same steps.

If the lab could prove the blood was human, we were hoping they could spin DNA from it – which potentially could be tested against hair samples from the found child said to be Adam, kept by the Broward Medical Examiner.

We couldn’t convince Hollywood Police to go into the room, but we did get Metro-Dade Police to go in. I spoke to homicide detective Ed Carmody, who was Jan’s friend.

“It’s a big enough whodunit for the police. All the linkage to Dahmer warrants us taking a good look at it. I couldn’t go on with my daily work thinking of that meter room.

“If we didn’t do it, we’d be like the Keystone Kops.”

But the next day, Carmody spoke to the shopping center owner, who told him, “You guys are just wasting your time.” There had been a fire in October 1994 which destroyed 70% of the shopping center, he said. The electrical room was “caught up in the fire,” and had been covered by soot, dust, and water. They’d since cleaned, replastered, and redone the room.

Carmody told me he was on his way to see the owner when his boss told him to turn back.

Geoff and I talked about it. The fuse boxes were near the entrance, away from the wall with the blood spatter, and we hadn’t seen any soot on the ceiling. He’d heard that the fire had been in the movie theater, which was away from the electrical room.

The fire had done some destruction but less than 70% of the shopping center was badly damaged. But how about in the electrical room?

When I’d passed the fuse boxes, on them I’d caught sight of something I hadn’t seen for decades: handwriting in fountain pen ink. I remembered, in first grade we couldn’t have pens, then in second grade we all had to buy these awful fountain pens with liquid ink cartridge refills, which stained our fingers. Recognizing it dated me as well as the boxes. And in fact, the shopping center had been built in 1957:

There were some newer fuse boxes also, but the fire hadn’t affected the oldest ones.

The lab results came back about two weeks later, and the news was uninspiring: the samples, as biological material, had degraded and could tell us nothing. Probably because they had been in that warm, humid, windowless room for so long, they simply weren’t testable.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

Episode 32: “They were trying to scare us not to run the piece.”

We’re only in Part 3, of 6 parts, the Jeffrey Dahmer section. SUBSCRIBE now for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. Maybe you might consider paying for a subscription?

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular, @investigative, @acosta, #criminology

🧐