Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

My friend Steve Votra was funny. He called himself “The Shadow,” a reference to what he said was his talent to be present but not seen, which itself was a reference to the old-time radio serial about a wealthy man who devoted his life to fighting crime as a private detective, once played by Orson Welles. His signature line was: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!”

Steve was the real thing – at least, I think so. I was always careful not to ask him too much, and only let him tell me what he was comfortable with saying. Just by talking with a journalist, even for friendly background, he was betraying some client confidentiality. And loose lips, after all, can bring prosecutions, even years later.

I did ask him whether he was John Monahan’s gorilla. No, he said, he wasn’t. He said he met Monahan’s gorilla at Herby Meier’s funeral. He didn’t name him, and I hadn’t asked.

Anyway, Steve himself wasn’t a gorilla – he was way too small – but implied under his easy laugh and friendly exterior was a tough guy inside, someone not to mess with. Which I had no intention of doing.

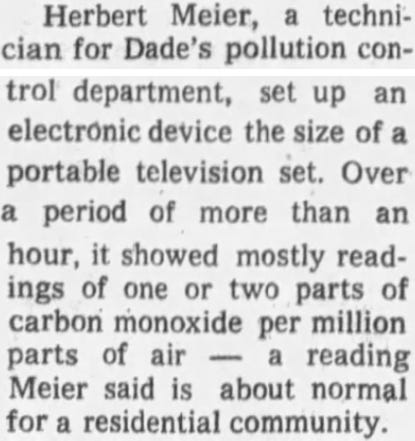

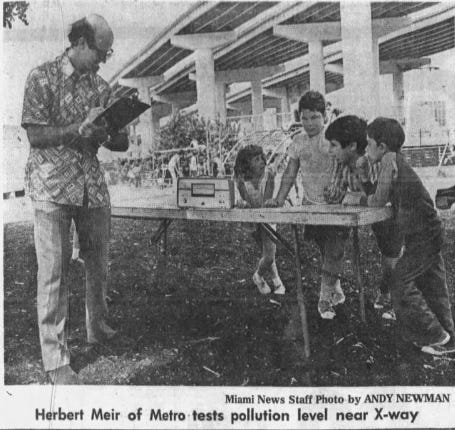

Herby was his friend, as the death certificate states. He said he knew that he was flying out there and had spoken to him days before going. Herby was an “electronics whiz, a wizard,” he said, which I confirmed by this newspaper story seven years before:

“He had a fucking IQ that wouldn’t quit,” Steve said. “But he was a twisted, warped MF.”

A reason for the trip, he said, was to carry “all the sophisticated electronics to do what they did,” — which was to do “wiretap and surveillance things” for Monahan.

“They were doing counterintelligence – helping Monahan defeat who’s looking at him, like the DEA.”

The DEA and other law enforcement agencies were looking at two things. Next in my notebook, dated days later, former Denver Post investigative reporter Lou Kilzer told me that “one of the fugitives that the feds were watching at Rivenbark’s Black Mountain Ranch was Carmine Persico” – Carmine the Snake, the head of the Colombo crime family. Referring to another fugitive at the ranch, I also wrote, “Colombo family hitman.”

(Hey – you mean your family doesn’t have a family hitman?)

The other issue was, as my notes read, “Votra knew that they were drug smugglers. He knew they had used that plane to make a run or two. The DEA was watching it everywhere. Following it in the air, on the ground.”

“I’m sure they slapped something on the bottom of that jet,” he said. “They were just watching and waiting.”

I asked who that might have been. He answered, U.S. Customs, the Marshals Service, the FBI.

I asked, did they know they were being followed?

“If they didn’t, they were stupid.”

Steve told me these were “really bad guys he was running around with.” He told his friend, days before the flight, “Herby – a smart Jewish boy doesn’t do (these) things.”

After he heard that the plane went down, Steve flew to Denver on a commercial flight. At the morgue he identified him by a ring he was wearing, which Steve brought back for Herby’s wife.

Herby was also carrying a roll of gold coins (Eagles), and a Walther PPK.

“I flew out there and brought him home in a fucking cardboard box,” he said.

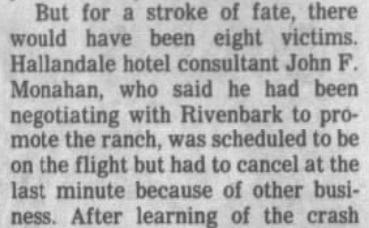

The Sun-Sentinel had asked Monahan about the crash. He’d told them he was working on a deal with Rivenbark to promote his ranch:

Steve called Monahan “a player, and one of the boys,” and always looked at him “with a jaundiced eye.”

“I kept my distance from him. I wasn’t afraid of him. I had my gun. Every time you’re around them (a reference to Monahan and now I’m thinking, maybe Rivenbark), you wanted to take a shower.”

My notes don’t reflect other good questions I may have hesitated to ask: Why were you around them? Why did you know them?

“Monahan does not make mistakes,” he said. He’s “too fucking calibrating.”

Despite Steve’s use of the present tense, Monahan had died ten years before, in 2004.

Colorado was Monahan’s second time in three months he identified bodies at a morgue. In August 1981, John Walsh had asked him to go to the morgue in Indian River County to see if he could identify the remains of the child found in a canal there. Monahan said he recognized the head as Adam’s.

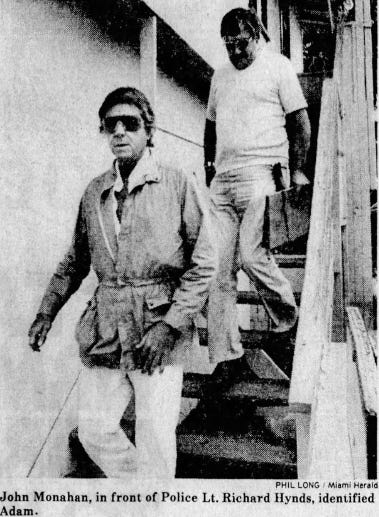

“A burly man in a khaki jacket, Monahan was trembling as he left the morgue,” The Miami Herald reported. Leaving the portable, the Herald reporter photographed him.

Um, August. Does anyone know how f-ing hot and humid it is here then? I do. And I will tell you that in the summer here no one wears a long-sleeved, buttoned-up jacket. In the daytime heat and sunshine. The man behind him is wearing a white T-shirt. That’s the Hollywood police lieutenant.

In the two TV movies, Walsh’s character is shown at work with partners in a hotel management company, one of whom was named, with his real name. But Monahan was never portrayed, named, mentioned, nor referred to. In the first movie, when the found child was identified, it didn’t have Walsh arranging to send anyone to the morgue, and definitely not Monahan.

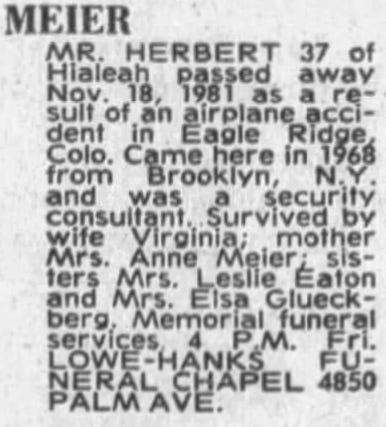

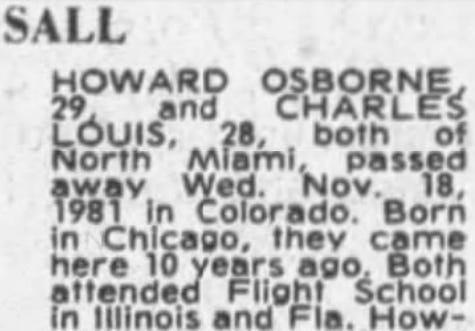

Did Walsh personally know any of the plane crash victims? If the surviving family of the pilots didn’t know him, they certainly knew who he was. In their newspaper-published death notice, they asked that in lieu of flowers, donations be made to a missing children’s charity that the Walshes were then working with:

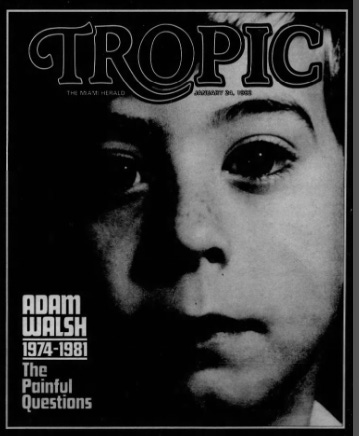

Two months after the plane went down, the Herald ran a Sunday magazine cover story about Adam. Reporters visited John Walsh at his office in Bal Harbour, which was across a hallway from John Monahan. The story didn’t mention the crash; apparently neither Monahan nor Walsh told them about it, and there was no reason the reporters on their own would have realized a connection. The Herald had reported on the crash but without the context that came a year later, in another local newspaper.

It was unlikely that Walsh didn’t know Shelly Stock, Monahan’s fiancée and co-worker, nor wasn’t aware that she’d been killed.

And the Herald reporters spoke to Monahan. They’d quoted him recalling how he’d identified the remains as Adam, and speaking about Reve:

Years later, unable to pursue the story further, Lou Kilzer offered his notes to a former colleague at the Denver Post, Jay Grelen, who had since become a local columnist in Mobile, Alabama, at the Press Register newspaper.

Grelen talked his editor into saying yes to an expensive, lengthy, longshot proposition on a story that had no local angle for Mobile. For a midsize city newspaper, to say this happened even rarely would be an exaggeration, but Grelen was a personal friend of his editor.

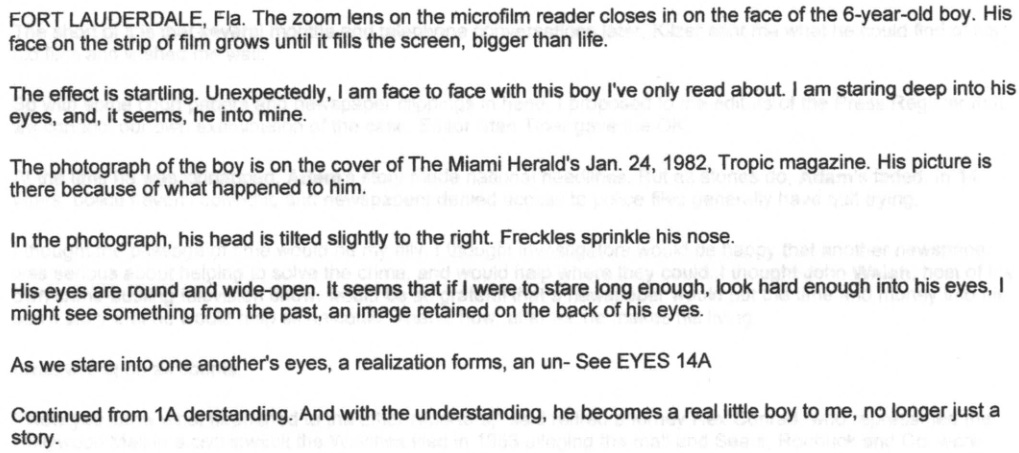

For three weeks Grelen camped out in South Florida to see if he could discover anything new about the case. In May 1995 he wrote that his pursuit became clear to him on the night he began researching microfilm of old newspaper stories in the Broward County main library, in Fort Lauderdale:

Grelen expected the police would be pleased, and John Walsh grateful, for a newspaper’s extended investigation more than a decade later, and that they would help him.

“I was wrong on all counts,” he wrote. The Walshes wouldn’t even speak to him, despite his repeated attempts to contact them.

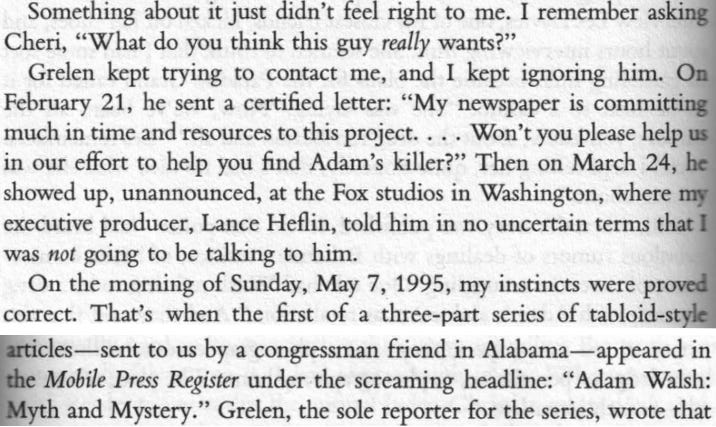

Walsh was famous in the media for doing interviews and publicity about himself and Adam’s story. But in most if not all of those interviews he was allowed to control the narrative. In his 1997 book Tears of Rage, John Walsh wrote of when his assistant told him that Grelen was interested in the story:

This is what Grelen had written:

Actually, the Hollywood Police chief in 1996 had said the same.

The series mostly covered what had already been reported, but much of what Grelen wrote was critical of the Walshes:

John Monahan also refused Grelen’s interview request. After the series ran, Monahan did speak to The Miami Herald:

But Monahan did tell him one thing, Grelen wrote:

Monahan would turn out to be right – but for reasons that couldn’t then have been foreseen.

In 1984, Monahan had recalled yet another tragedy close to him, the death of his young wife in 1976:

Peggy was a socialite, her name was in the local society pages about a dozen times. Three years before her death, she and John had taken a jungle safari:

Again, this interview was in 1984. Monahan mentioned having relationships but not that his fiancée had also since died a terrible death.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child: