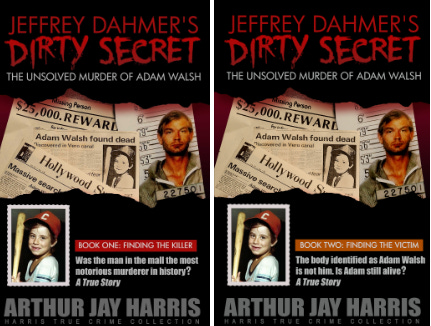

The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 34

Episode 34: Were the four new witnesses at the mall credible?

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

I found the new witnesses right away. In the order in which I reached them:

Phillip Lohr

A 1997 summary memo written by Phil Mundy attached to an interview he’d done with Phillip Lohr was dismissive. Lohr had already sought out Mark Smith, who told him what he’d seen had had no relation to Adam. Lohr had complained to Smith’s sergeant, then found Mundy. Mundy agreed with Smith. When Lohr got sarcastic, Mundy wrote, he decided to just take his statement.

Mundy wrote that Lohr couldn’t say for sure he saw Adam, couldn’t be certain it was on the same day as the abduction, and his description of the man he saw didn’t fit Toole “or any of our other ‘suspects.’”

In the transcript of his statement, Lohr said he’d passed a man carrying a child out the lawn and garden entrance of Sears, and overheard the child say something unnerving:

The child was about six. For Lohr’s comparison, in 1997 his own son was six. The child had a freckled face, brown hair, was missing his front teeth, and looked flustered, like he’d been crying. Lohr couldn’t be certain of the day it happened, but recalled it had been a day or so before he first heard the news about Adam missing and had seen search helicopters flying. The time could have been anywhere from noon to 3.

The man, he described, was about 25-30, 6-foot, medium build, brown hair, wearing glasses, and had sideburns and a “short chin beard” connected to a mustache, possibly like a goatee.

He said when he saw Adam’s picture on the news he immediately thought, “you know, did what I see, could that have possibly been Adam?”

Mundy asked why he didn’t immediately contact the police.

Mundy asked why he was talking to the police now.

He’d seen a blue van parked in a traffic lane within twenty feet of the store entrance, and no one had been in it. To his annoyance it had interrupted the traffic flow. He didn’t know if it was connected to what he’d seen moments later.

On that, Mundy ended the statement.

Toole had a white Cadillac; rightly or not, Timothy Pottenberg’s blue van sighting had been discredited. So had Bill Bowen’s blue van. When Lohr brought up a blue van, Mundy seemed not to want to hear about it.

I, however, was very interested in a sighting of a blue van. Although Lohr recalled it as somewhat deluxe, as had Pottenberg, he’d also placed it in nearly the same spot as Bowen and maybe Pottenberg had said it was.

“I know absolutely it was Adam Walsh” who I saw, Lohr gushed when I came to his Hollywood home to see him. He was also “absolutely positive there was a blue van.”

He’d expected someone to contact him after the Hollywood press conference. He was equally positive that Toole was the wrong man.

I took his story from the top. He was a regular shopper in Sears’s tool department. That day in 1981, driving in the parking lot lane next to the west side of Sears, headed south, Lohr had spotted a good parking space. Next to him in the northbound lane was a blue van, inappropriately parked and stopping traffic. A county bus was behind the blue van and then a white car, possibly a Ford (not a Cadillac, he insisted). He was about to make a right turn into the parking lane when from behind the bus the white car darted into his lane, cut him off and turned towards the spot.

Lohr was incensed – enough to animatedly recall it for me so many years later, as if it had just happened. It was weird but I understood. I knew from living in South Florida back then, you snuck into someone’s intended parking space at the risk of gun violence.

The white car didn’t take the spot but Lohr remained irate by the episode. On his way into the store he walked past the van, the root cause of the problem – it was right in front of the entrance, about 20 feet from the door.

As he passed through the door, a man exiting was carrying a child. Something was inappropriate; the child was about 6 years old, too big to be carried. And he was either crying or had just stopped. That child was Adam, he said after seeing his picture in the news.

“I heard Adam say, ‘You’re not my daddy.’” The man responded, “I’m taking you to your daddy.”

“It startled me. I thought, everybody down here is divorced. There’s a boyfriend. Okay, maybe he’s taking him to his daddy.” Stopped in his tracks, Lohr wondered, “Should I do something? Go out there and take a look?”

He didn’t follow them but did decide to commit to memory what he’d seen. He focused on the child. He noted his three-color striped shirt, khaki shorts, his face covered with freckles, and that his front teeth were missing. Also, “I remember saying to myself, sailor’s cap.” Later he called it a captain’s hat. “I thought, what kind of parents would give a kid a captain’s hat?”

All that matched Reve Walsh’s original description of Adam, except for the color of his shorts, which Reve had said were green. But khaki can be green or beige.

He didn’t concentrate as much on the man. All he could say was, “He was not really dirty. He had reasonably acceptable clothes, a neat appearance. I did not consider him to be unsavory.” He recalled that the man was wearing glasses, possibly sunglasses, and was maybe 6 feet tall, or in any event, a few inches taller than Lohr, who is 5’6”. He had a very calm voice.

“Oh God, could I have done something? Could I have stopped it? I don’t want to be known as the person who didn’t stop it,” he said. He repeated to me that he’s felt guilty all these years – although he realized that at the time he couldn’t be sure there was any reason to do anything. “Ever since Adam, I’ve stopped people when their kids say, I don’t want to go!”

In 1997, with the case back in the news, he saw another blue van driven by someone who made him think of the man who’d carried the child out of the store. Considering his own son, he thought, what if, “Oh my god, he’s back!”

He called Mark Smith at Hollywood Police and came in to give a statement. Smith gave him a photo of a small boy who looked like Adam but wasn’t, then left the room. Lohr got the feeling he wasn’t being taken seriously. At the State Attorney’s office he found Mundy, who showed him a six-photo lineup that included Toole. Lohr insisted Toole wasn’t the man.

I showed Lohr a photo of Toole from John Walsh’s book. “He ain’t got enough hair,” he said. “That is definitely not the person.”

I showed him Dahmer’s 1981 black-and-white mugshot. He was dubious. Then I showed him a color shot of Dahmer at his first appearance in a Milwaukee courtroom in 1991. He did a double take. Pending showing him more pictures, I left that day with his conclusion: “I can definitely say that I cannot rule out Dahmer, but I cannot rule him in.”

Lohr had an email address but warned me he wasn’t good with the Internet. I sent him links including A&E Biography’s Dahmer story, then realized he probably hadn’t opened them. Two weeks later I arranged to put him in front of a computer.

After a few minutes, he said, “For every picture I see that says, that looks like him, I see another that says, that’s not him.”

Dahmer’s 1981 mugshot came on the screen. I printed it, and Lohr borrowed a black felt pen and drew on it glasses, longer hair brushed to the side, and a mustache and goatee. “If I had a police officer set this down in front of me (in a photo lineup) and ask, can you I.D. any of these people, I would gravitate to that,” he said. “He has the eyes.”

A few pictures later, he added, “He’s demonstrated he has facial hair, and combs his hair over,” as Lohr had just drawn. He was looking for a shot of him wearing glasses, if possible photochromic lenses, which in sunlight darken to sunglasses. Lohr called them PhotoGray, a brand name.

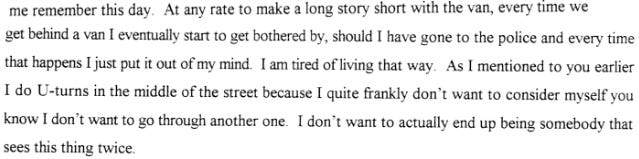

And then we came across a family portrait, first published in Lionel Dahmer’s book A Father’s Story. Jeffrey was about 17 (which would make it 1977), wore his thickest mustache, and a hint of hair lined the bottom of his chin (although it might have been only a shadow on the photo). He also was wearing dark amber glasses. Lohr stopped.

“Oh… my… god. That’s getting real close. And he’s wearing sunglasses indoors.”

He thought about it for the next few minutes. “I find it amazing how similar (that picture) is to the man I saw. You have a picture that is very, very similar.” He wouldn’t commit to certainty, but he repeated about the “striking similarities.”

“I only saw the man for a split second while I was doing the left/right dance to get around him, when I heard Adam say, You’re not my daddy.

“I’m amazed that Jeffrey Dahmer could be that similar to the person I saw. Seeing that picture there starts making it real creepy.”

I later asked Billy Capshaw whether Dahmer had ever worn transition glasses. He had. “They were a smoky color when they changed,” he said. “I had never seen glasses like these, I was pretty impressed with them.” He remembered they weren’t army-issue, and were in the 1970s style of aviator glasses, square-looking. That description matched the glasses in Dahmer’s family picture.

Vernon Jones

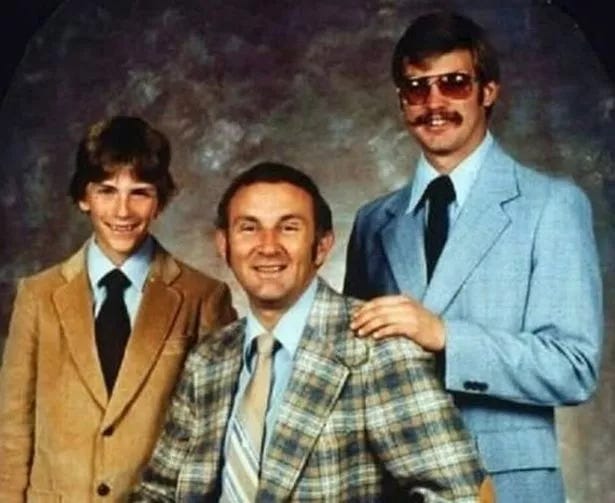

In 1994, Vernon Jones wrote a letter addressed to John and Reve Walsh in care of John’s show:

In 1981, Jones was nine. He offered a further explanation to the Walshes or anyone who would get back to him. He wrote that he’d just spoken to 1500 people at a convention for a group called Youth Crime Watch and told them that what had happened to Adam “could have been me” instead, or it might have happened to both of them together.

America’s Most Wanted forwarded the letter to Hollywood Police, which didn’t call him. In 1996 Phil Mundy found it in the file and went to Jones’s office in Miami to speak to him. Jones was then working for a youth crime prevention program funded by the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of Florida. On audiotape, he and Mundy spoke for fifteen minutes:

Moments later:

Later, Vernon’s parents showed him a news story about Adam:

Mundy showed him the photo lineup that included Toole, but Jones couldn’t pick out the man he’d seen. Mundy didn’t ask him whether he and his grandfather had made such a report, and instead thanked him and ended the statement there.

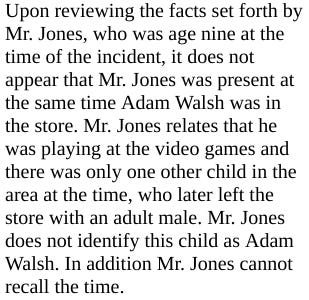

In his summary, Mundy wrote that Jones didn’t match what Mary Hagan and Kathryn Shaffer-Barrack had told him:

Jones was anxious to talk to me and had a lot to say. It was definitely Adam who he’d played with. He’d been telling that to people for years, even in other speeches he’d made to Youth Crime Watch groups. He’d even mentioned it to U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno and Florida Senator Bob Graham when they were honored by the organization, and a number of local police chiefs. That the man he saw wasn’t Toole, that was true.

Adam’s murder changed Jones’s life. He knew how close he’d come to Adam’s fate. The man had motioned to either or both of them, and what probably saved Jones was that he was three years older than Adam, plus Jones is Black and the man was White. He told me he thought, “Oh, man, I’m not goin’ with you,” and turned away.

Just after that, Jones’s parents enrolled him at a karate school for kids, to learn self-protection. Five years later, Jones opened his own karate school for kids, which he still had. He earned a black belt and taught his dad to be a black belt.

That summer he was staying with his 78-year-old grandfather Otis Williams at his home in Hallandale, next to Hollywood. They got up early each weekday to cut lawns. Often they would go to Sears because Williams needed to replace a broken blade or some other yard tool. While he shopped in the tool department, Vernon played video games.

That particular day he was playing Intellivision’s baseball game with Adam. They were both standing, Vernon on the left, Adam on his right. It was the last inning, Adam trailing but he was up and had the bases loaded.

That was the moment that the man tried to get their attention. Or was it just Adam’s attention? Vernon thought he remembered hearing a noise, like Hey, hey.

“I looked over, you talking to me? I didn’t know him,” he said.

Distracted, Vernon returned to the game. “I pitched the ball. Crack! Grand slam home run! Oh, man!”

He remembered Adam’s smile at having beaten the bigger boy. As the loser, Vernon put down his controls and moved around the side to another game in the store’s display, probably Donkey Kong. A bit later he looked to his right and saw Adam leaving with the man. There was contact between them, possibly the man’s right hand holding Adam’s left hand.

He couldn’t remember if it was the same night or just after when an aunt called his grandfather to turn on the TV news about a little boy missing from Sears. At least two of Vernon’s aunts worked either at Sears or elsewhere at Hollywood Mall.

He remembered seeing Adam’s picture. “Grandpa, grandpa, that’s the boy I was playing with,” he said. “Are you sure?” he asked. “Yes, sir.”

Next morning, before starting work, his grandfather took him to the Hollywood Police station.

“I’ll never forget it. Parked the truck, getting out, walk the walkway, holding his hand.” An officer was “hanging out” and Vernon’s grandfather “literally ran into him, bumped into him.” Vernon explained that his grandfather always had a fast walk.

“I’m sorry, sir,” his grandfather excused himself. Vernon never knew the officer’s name, but remembered his gun belt and his belly. It was Vernon’s first encounter with a police officer. “My boy here, my son here…” his grandfather tried to say.

The officer spit a black wad of what might have been tobacco at Vernon’s grandfather’s feet. It hit the ground but splattered back onto his shoe.

“Listen boy,” said the officer, “I don’t have time for this.”

“I’m sorry, sir,” said Vernon’s grandfather, who grabbed Vernon’s hand again. They turned around, walked back to the truck, and went to their first job that morning, cutting a lawn in Bal Harbour.

Vernon said that was the first time he’d encountered racism. “Why was he calling my grandfather ‘boy’?” he wondered then. The result was, Hollywood Police never got his tip.

I showed him a Toole picture. “Uh uh,” he said. “I would have remembered a face like that.” Then I showed him a 1991 courtroom shot of Dahmer.

“Wow,” he said.

I put him in front of my computer screen and played MSNBC’s 1994 prison interview with Dahmer. He stared, rapt. He knew who Dahmer was but hadn’t associated his face.

I watched what was happening to him. He narrated for himself:

“Looking at him, hearing his voice is bothering me. I feel my eye twitching, I feel my heart rate elevating. Looking at him right now, putting the headphone on and hearing his voice is literally bothering me.”

As well, his voice was breaking, and the eyes of this black belt karate instructor were tearing. “When I heard the case being closed, my family and others know I’ve been talking about this for years…” he trailed off.

“Looking at him, I wouldn’t have been scared. The other guy [Toole], I would have gone ecch, get away from me. He was revolting.”

Janice Santamassino

On September 21, 1996, the night America’s Most Wanted ran what was supposed to be its last-ever segment, a full hour about Adam’s case, a show operator taking tips wrote this down:

Hollywood, Fl. Caller saw by toy entrance a dk color van was parked there (maybe blue) w/curtains in windows (old beat up van). It was around 11 A.M. (morning hours). Caller reported this information to Hollywood Police that night Adam disappeared. Caller had seen Adam playing near the arcade when she walked in, and 10-15 mins later she heard on the loudspeaker he was missing.

The caller left her name and phone number.

It was the same night Mary Hagan had called. The show had forwarded the tips to Hollywood Police, along with others as they’d gotten them. There was nothing in the case file to show that Hollywood had called back her or Hagan. Phil Mundy had found Hagan, but hadn’t mentioned this caller to me, nor was it in his file.

I found her easily. Her name was Janice Santamassino, and in fact my call was the first time anyone had ever gotten back to her about Adam Walsh. No one had called her back in 1981, either.

She first wanted to talk about the van. Before she’d entered the store, it had been inappropriately parked directly in front of the toy department entrance, and while driving, trying to get around she’d almost rammed it. She’d gotten her first driver’s license only months before; “I wasn’t too good at making turns then,” she said.

She was so upset about the van that she’d tried to remember its license plate number, to tell the police. That afternoon, when she’d called Hollywood immediately after seeing Adam’s photo on the 5 o’clock news to tell them that was the boy she’d seen, she’d mentioned the van to an officer, even volunteering that if they’d arrange a hypnotism session she possibly could recall the whole plate number. Twenty-seven years later, the letters and number still in her head were K, L, and 6. The only other description of the van she could add, besides what the show tip line operator had written down 12 years before, was that it may have had heart-shaped windows in the rear, covered by a curtain.

She described Sears that morning as “relatively like a morgue – empty. The only person I saw was Adam.” She estimated it was between 10 to noon. She had brought her 11-year-old son Anthony and 4-year-old daughter Lori to buy little girls’ white sandals. That July Monday was the first day of Janice’s vacation, and she’d planned to spend the rest of the day poolside with the kids.

Walking through Sears on their way to Kinney Shoes, they passed the videogame display. Lori wanted to play.

Adam was already playing, Janice remembered. “The kid was talking about the video. He was telling her how it worked. She had her hands on the game. We were there a good ten minutes – too long, I thought. She wanted to stay with him. I thought it was a little strange, the boy being there alone, so long.”

She remembered Adam wearing a cap – she thought it was a baseball cap, maybe blue or red or white.

Lori, then 31 and married, told me she had a memory of it too:

“He was standing to my left. It was a game with a joystick, I remember where his hand was, on the joystick. I was watching him play. I just remember, it was me and him. He was slightly taller.”

“I wanted to pull her away from that game,” Janice said. Lori had responded, “Five more minutes!”

“No!” said Janice.

Leaving the games they walked through the toy department, Janice holding Lori’s hand. There was a man with his head down holding a toy, possibly reading it. He looked up at Janice and briefly their eyes locked.

“I remember thinking he was weird” and out of place, she said. “He was scuzzy and he had no kid with him. I had a creepy feeling.”

She described him: disheveled, unshaven, no mustache, thin face, no glasses, about 6-feet tall and lanky, in his 30s. His hair was brownish or sandy-brown, and “was a wreck. He was scary-looking.” I asked if she was scared of him. “Now that you mention it, yes, for a fleeting moment.”

She’d seen Ottis Toole’s picture – obviously, since she’d watched that episode of America’s Most Wanted – and although she said she couldn’t be 100% sure, she thought it was Toole.

They’d gotten to Kinney Shoes but when Janice found they didn’t have the white sandals she was looking for, they went back to Sears and saw a pair in its shoe department. When I came to meet Janice at her home, she showed me the shoebox they’d come in, now stuffed with old bills. Sears’s price tag was still on it: $4.99, children’s size eight and a half.

While back in Sears, she recalled hearing the store’s public address page for Adam, missing. On her way toward the garden center exit, passing the catalog desk, she saw a woman who she figured was the mother of the missing boy. “She looked distressed, crying or about to cry,” she said. She was leaning on the counter with one hand, the other hand holding what Janice remembered was a lampshade or a lamp. Her hair was disheveled, like she’d just gotten out of bed.

She was with someone, “I thought, a husband, a friend.” His hair was similarly disheveled. She described him as late 20s to early 30s, dark hair. Janice left the store, expecting that the child would show up. Maybe he was just hiding.

On television, Janice recognized John Walsh. She knew him because she’d worked at the Diplomat Hotel for a number of years and remembered he’d worked for the hotel’s convention services; she’d seen him in the catering department. He was good-looking, she added.

But the man she’d seen with Reve at the catalog desk wasn’t John. When I showed her two newspaper photos of Jimmy Campbell she said it might have been him.

I was more interested in the man in the toy aisle. She had gotten two good looks at him; his profile and straight on. On her computer screen I found MSNBC’s 1994 prison interview of Dahmer, by Stone Phillips, and played a few seconds.

“He’s got the right nose,” she said.

I skipped to A&E Biography’s Dahmer show. They had him walking into a Milwaukee courtroom for his first appearance.

“That’s his profile!” She got excited. “His hair. That’s what I saw, when he was looking down. I can’t believe it, this is like the profile.”

I found Dahmer’s 1991 color mugshot, with both a profile and a forward shot.

“That’s it! His hair was a little bit more messier. I’m getting goosebumps.” She was; I saw them on her arms. “I never thought I would get that emotional. But that is him. That looks like him. I can’t believe it! I was 99% sure it was Toole until I saw this.”

We talked about the forward-looking mugshot. “That’s what I saw, at me.” I said others had told me that Dahmer could look right through you. “Right!” she said. That’s what she thought he was doing in the mugshot, and when they’d locked eyes.

“Wow. It’s so eerie looking at him. He’s scary.”

Jennie Warren

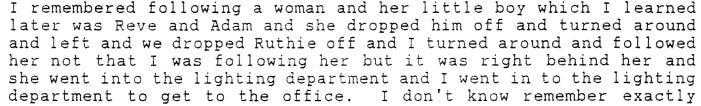

A report by Mark Smith briefly detailed a phone call he got from Jennie Warren on October 30, 1995. She was then 72. She told him she’d never before spoken about Adam’s case to Hollywood Police. She said that on the day of the abduction she was in Sears with her 8-year-old granddaughter and had seen Reve and Adam enter the store from the catalog desk door. Reve then left Adam at the video games.

Several children were already playing the games, so Adam had to wait his turn. Mrs. Warren left her granddaughter in the toy department, then followed Reve as she walked toward the lamp department. Mrs. Warren continued on to the store’s business office. When she returned to Toys, she saw a suspicious man who she described as 5’9”, in his thirties, dirty blond hair, wearing a khaki-colored shirt and pants. He was talking with a catalog department employee who she knew. Although she felt “uneasy” about the man in khakis, she didn’t think much of it and left the area with her granddaughter. About 30-40 minutes later she heard an intercom page for a missing child.

Smith had tried to find the catalog desk employee who had been talking to the man. Sears referred him to two men, both of whom said they hadn’t worked on the day of the abduction.

Almost a year after Mrs. Warren called Smith, Phil Mundy taped an interview with her.

First, Mrs. Warren said she’d gone to Sears with not one granddaughter but three, ages 14, 8, and 3, the youngest in a stroller. It was “between mid-morning and mid-afternoon.” They’d entered on the west side and had first gone to Toys, where the 8-year-old wanted to look at Barbie dolls.

At the videogames she’d seen Adam standing behind two boys about 12 years old, watching them play. As for the man in khakis, Smith had written that Mrs. Warren saw him when she returned to the area, but she told Mundy she saw him before she left:

Although the man in khakis and the catalog department employee were talking while watching the boys play the game, she described the khakis man as “alone.”

“He was just standing there watching,” she said, his hands in his pockets.

After Reve went into the lamp department, Mrs. Warren continued on to the business office to pay her Sears bill. She took a service ticket but the wait was going to be long and she felt uneasy about leaving her 8-year-old alone for all that time.

Let’s go, she told her 14-year-old. When she didn’t move fast enough, Mrs. Warren threatened to kick her in the rear to get her going.

Back to the toy department, she hollered for the 8-year-old, who answered. She didn’t notice whether the khakis man was still there. They left Sears and went into the mall, then later heard a store announcement about a lost child. Mrs. Warren took the moment to lecture her 14-year-old on why you shouldn’t leave a child alone.

Mrs. Warren was an astute observer of hair. She was a hairdresser, and could recall about Reve’s hair: it was damaged, probably bleached and permed, straight at the roots and frizzy at the ends, like she was trying to grow it out. All she could remember about Adam was that he wore dark clothes, nor was she sure about any head wear. “But I know he was engrossed in watching the Nintendo,” as she called the video games.

As for the man in khakis:

Mundy showed her his six-picture lineup that included Toole. She picked out Toole but not, as Mundy wrote, to identify him. She said Toole’s picture gave her “a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach when I saw him but I can’t really say that was his face.”

I met her at the doorstep of her Hollywood home. At the mere mention of the case, Jennie, then 85, began to cry. Blubber. She knew that the man the Hollywood Police had just decided killed Adam was the wrong man. It was the other guy.

Jeffrey Dahmer.

She couldn’t say exactly when she’d made the Dahmer connection. But her grandson-in-law, married for the last ten years to the granddaughter who’d been 14 in 1981, told me she’d said it to the family a few times.

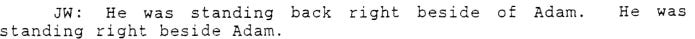

The story she told me of her day at Sears was consistent with what she’d told Mundy except she named the man in the khakis as Dahmer. At the computer games, Dahmer was there when Adam arrived. The two boys already playing were White, and Dahmer was standing right behind them. Adam took a place on Dahmer’s left, and they both watched the game.

“Adam could have cared less who he was next to,” she said. “He was wanting to play the games.” Did Reve see Dahmer too? She must have, Jennie answered, “I was right behind her.” Reve also must have seen the catalog department employee, she said.

Did she see you? Probably not, Jennie said. “Reve was all wrapped up in herself.”

Since the man she said was Dahmer was wearing army-type clothes, did she think he’d been in the army? Yes, she said. Bill Bowen had described the man he’d seen outside as wearing an army shirt, but said it was green. Khaki meant beige, she said. Bowen also said Dahmer was wearing a baseball cap.

“He was kind of shy,” she said. “His expression was, he was sad, or lonely. After I left I had the sense he was intent on watching the boys.”

We looked at Milwaukee courtroom pictures of Dahmer. “See where his hair is? It came that far down, below his ears.” To another one, she said, “The hair, the beard, an overgrowth. That’s him.”

To the picture on the cover of a book about Dahmer, she said, “That’s the man I saw. All these pictures, he has hair below his ears. I’m a beautician, and I notice all these things.”

I showed her a picture of Toole. “That’s not him. He’s ugly. This Dahmer was not ugly.”

At Sears’s business office, when she decided she needed to retrieve her 8-year-old, she told the 14-year-old to hurry up. When she didn’t, Jennie said, “No! I want to get back there, let’s go!” When the girl still didn’t react, she threatened, “I’m going to kick you in the buttinski if you don’t move!”

Back in the toy department Jennie called the 8-year-old’s name. “Yes, I’m here! What do you want?” she answered.

“Come here!”

“But I want to see the dolls!”

“Come here right now!”

“Okay, nanny.”

Of the four new witnesses, one had first contacted authorities in 1995 and the other in 1997, but the other two had tried to tell Hollywood Police what they’d seen within the first days of the case. That made six witnesses at Sears that day who saw Adam’s possible abductor and said they’d gone to Hollywood Police with their tips in 1981: Santamassino and Jones, Morgan and Bowen, Mary Hagan and Timothy Pottenberg. All but Morgan said they saw Adam as well. Actually, although Timothy reported seeing a small child, he did not explicitly tell the police it was Adam.

Here was the problem: of the six, the original detectives only knew of Pottenberg. Actually, he was the only one of the six who hadn’t on their own volunteered or tried to volunteer their information to the police. His grandmother had brought him. Then they dismissed him – as police would eventually dismiss, ignore, or repulse four of the other five, excepting Mary Hagan, the Toole witness, by Phil Mundy.

Had the police had all six from the very beginning, in 1981 they could have shown them lineups which included Campbell; in 1983, Toole; and in 1991, Dahmer.

In the end, no votes for Campbell, probably one vote for Toole, probably five votes for Dahmer.

I expect that the case would have been over in 1991.

Campbell would have been eliminated early on, and Toole probably the same. Dahmer would have gone to trial and faced Florida’s death penalty, which he didn’t in Wisconsin or Ohio. In all the years after, the Walshes would have been spared so much additional grief. And the citizens of Hollywood and Broward County wouldn’t have had to pay for all that additional police work, documented in this story.

What seemed increasingly obvious through all my work was now certain: The Hollywood Police blew this case beginning on the very first day, when Janice Santamassino called them at 5 o’clock with what she knew and wasn’t called back. The cops also blew it every day after, culminating on the day in December 2008 when the chief closed the case on Toole, choosing to overlook the most important witnesses who even gave them second chances to listen to them.

John Walsh said it himself, in 1982:

Walsh was wrong about Toole in 1996 and after. But give him credit, in 1991 and 1992 he was right about Jeffrey Dahmer. He let the cops talk him out of it.

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

You’re really far now, you’ll want to keep reading, there’s so much more about this story you had no idea about. And now we’re getting into the Jeffrey Dahmer section. FOLLOW, or SUBSCRIBE now for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. But if you’re the type who pays for subscriptions on Substack, maybe you might consider me too? (I wouldn’t mind in the least.)

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular, #investigative