The Unsolved Murder of Adam Walsh - 26

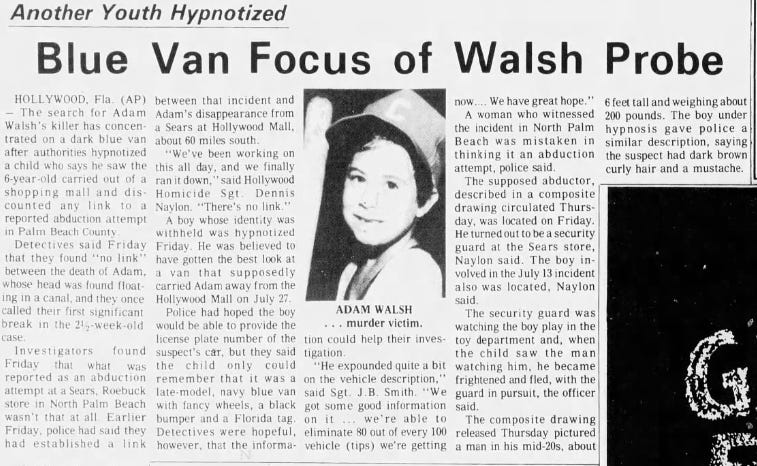

Episode 26: The blue van, that Hollywood Police could never find

Link to Episode 25: The quote of the year: Interviewed talking about his last murder victim, a child he found in a mall who happened to be the younger brother of a boy he’d been convicted of sexually assaulting, Jeffrey Dahmer said, “I didn’t know him from Adam.” Six months earlier, Dahmer had been asked if he’d killed Adam Walsh.

Or start at the series beginning and binge from there: (Link to Episode 1)

Given a proverbial if not literal second chance at life, Darlene and her new, sort of accidental husband Larry, a gay man, struck up a friendship. Larry was kind and generous to her as well as to her daughters, Denise and Robin. He helped pay for Darlene’s hospitalization and set her up in a strip mall storefront restaurant she called Sunshine, a lunch place serving salad and homemade soup. That was in the 170th Street shopping center, blocks south of Larry’s Beach Pizza.

You’ve already seen the certificate of Darlene’s marriage to Tex, in August 1980. She married him while staying friends with Larry and not exactly divorcing him (don’t make me explain) – something out of courtesy while she was alive that I hadn’t put in print. By March 1981, she and Tex sold Sunshine to Larry, who remade the shop into Sunshine Subs. She and Tex took off for the road as haulers in the semi-trailer truck they bought, but when they’d return home to Miami they kept tabs on both of Larry’s places.

When their mother left, Denise and Robin went separate places to live. Since Denise had worked at Sunshine, in April 1981 she went to work for Larry and stayed at his condo, also blocks from the ocean.

“If Dahmer was on that beach, my girls would know it,” Darlene volunteered. They knew every teenage boy within a radius, she said. She emailed them Dahmer’s mugshot but neither recognized it.

Nor did they know the name Houleb. Denise remembered a Ken, a mature man who made pizza deliveries for Larry.

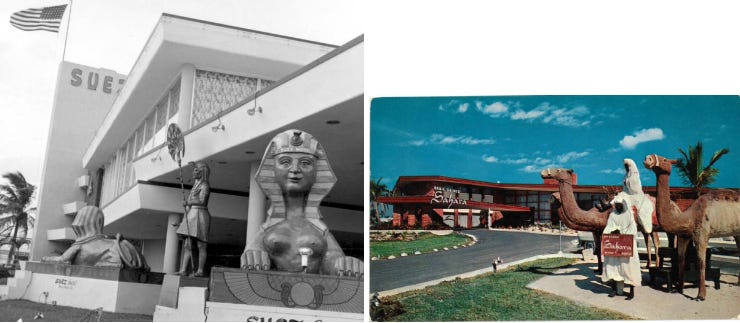

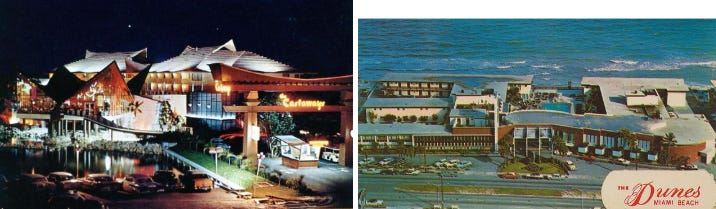

The 1981 phone book listing for Sunshine Sub had said pizza. Pizza – all the wonderful ticky-tack oceanside tourist hotels on Collins in Sunny Isles – deliveries.

Why hadn’t I made the connection? Deliveries – vehicles. To Jack Hoffman, Dahmer’s credible claim that he didn’t have wheels was his main alibi why he couldn’t have gotten from Collins Avenue, on the beach, to Hollywood Mall, inland. But Larry’s main place made deliveries. Might “Sunshine Sub – pizza” have as well? Might Dahmer have made deliveries in a vehicle perhaps owned by Sunshine Sub or Larry’s place up the street?

In his interview, Dahmer never mentioned pizza. Had Hoffman gone to the Miami main library, might he have made the connection, in 1991 or ’92?

I asked Darlene to ask Denise, Could she remember whether either of Larry’s stores had delivery vehicles? The answer returned: three. One was a Ford Escort car, the other two were vans: a white one and a blue one.

A blue van, at the sister store where Jeffrey Dahmer worked, 15 minutes from Hollywood Mall?

Darlene remembered it too. She’d used it when she moved, five times between summer 1979, after she left the hospital, and the end of March 1981, when she put her things in storage.

How easy was it, I asked, for drivers or just employees to take those vans?

“Easy,” she said. “Anybody could grab a key to those vehicles. Larry ran such a mess.”

I later found six others who knew of Larry’s two restaurants and remembered a blue van.

Unlike Sunshine in either of its iterations, Darlene said (not using the word iterations), Larry’s main place was a gold mine. It opened at six in the morning and closed at five in the morning, then later it never closed at all. At different times of the day and night it was a hangout for teens, college kids, tourists, and after-hours people. A big part of the business was delivery, which they did well into the middle of the night.

She said the store had a huge turnover of employees. Larry would hire gay and “off-color” people. If they didn’t have a place to sleep, he brought them home to sleep on his couch. That came “out of the goodness of his heart,” she said.

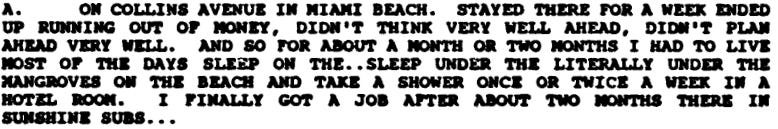

At the end of March 1981, the Army discharged Dahmer. He told Jack Hoffman they gave him a ticket for a one-way commercial flight to anywhere in the U.S., but instead of going home to Ohio and facing his father he’d chosen Miami, because it was warm – and Germany had been so cold. He took a room in a hotel, he couldn’t remember its name:

Did Larry, a gay man who brought drifters into his home, cross paths with Dahmer, a gay young drifter on the beach?

“Larry went places very late at night – I have no idea where he was,” Darlene said. “He never slept – or for two hours. I don’t know what he did, or where he did it, but he did it in good taste.”

Or so she’d thought.

“Larry was a generous person. He was helping down-and-out people. That’s what I’d like to think,” Denise told me. She realized only later that Larry was gay. She’d never seen him show any affectations, nor even physical contact toward anyone, male or female. She’d always felt safe with him.

The strays were always male and between 18-25 years old, she said. (In 1981, Dahmer was 21, Larry was 36.) Sunny Isles was then a magnet for runaways from all over the U.S. and Canada – like the more famous strip on Fort Lauderdale beach and the southern tip of Miami Beach, which was then decrepit. Every place was open all night, she said, and drifters were part of that life. When they needed work, Larry’s pizza place was a natural place to come.

Denise told me, that summer she worked weekdays until four A.M. and five on weekends, many weeks with no days off. She slept in Larry’s second bedroom, then woke up and discovered someone she’d never seen before asleep in the living room, or alone in Larry’s bed. She knew the drifter must have come in with Larry, but she never saw him touch any of them. “And I lived in the apartment.”

Larry didn’t drink or do drugs, although some of the drifters were alcoholics or drug addicts. She’d never seen any of them cause trouble. “They stayed various amounts of time – a week, a couple days, a month, longer. It depended on the amount of trouble they were in, if they were on the run.

“The amount of people through both stores – unbelievable. Most were addicted to drugs, drank, or were just here to party. They got money, then left.”

I asked about deliveries. At Sunshine, Dahmer had said he worked only inside the store, but did that mean he didn’t make deliveries?

“Employees weren’t limited to a single job. You did whatever you had to do,” she said. That included deliveries – for either store. On holidays, or when the hotels were full and a flood of orders came in, whoever could drive, did.

“I knew some people didn’t have licenses or had suspended licenses, or Canadian licenses. It wasn’t a concern to Larry.”

She said the white and the blue vans were the same model. They were spartan inside, just the two front bucket seats, and the rears were empty. The white was for fetching supplies for both stores. The blue was “Larry’s vehicle, for whoever needed it. Or if somebody wanted it for the night, whoever wanted it, took it.”

Did that include the drifters? “Yes, they had it too. A lot of times the drifters would just take a van and disappear for a day. I remember that van being taken and Larry not doing anything.”

She couldn’t remember the vans’ make and model, but they looked new. The blue was a medium blue. It had automatic transmission, AM-FM radio, AC, windows on the rear doors but not on the sides, and blue seats. “They were never kept clean, there was no maintenance. They ran until they became a problem,” she said.

Darlene thought the color was grayish-blue, or a darker blue, depending on the light. One van had only a driver’s seat, the other had only one additional seat. (Denise later agreed on one seat.) They were both extended vans, oversized.

“You have never in your life seen vehicles like these,” she said. “You’d need a tetanus shot to look at them. I told him, do you realize you’re delivering food? Do you know how unsanitary this is? This was a pigsty.”

Next I wanted to find Larry. Over the years since they’d all left South Florida, Darlene and her kids had lost touch with him. I checked the Miami phone book, and he wasn’t listed. Neither was his main restaurant. When I went downtown again to read microfilmed county records for hints of where I could find him, I saw he’d recently sold his condo. A Fort Lauderdale attorney had handled the contract.

I obviously wasn’t afraid of making cold calls, but since I’d have to leave a message with the attorney, I sensed this one might not be returned. I had enough trust in Darlene to ask her to make the call, guessing that she’d definitely get a callback. She agreed. When she called Larry’s attorney she left a message that there’d been a death in the family. That was real – her husband Glenn Hill, months before. Twenty minutes later, Larry called back, terrified.

They talked for a while, catching up. Larry had lost the restaurant and his condo, and was working for a church in Miami. To Darlene he sounded down-and-out.

Then she explained why she was calling: a journalist was pursuing the idea that Jeffrey Dahmer might have killed Adam Walsh, and Dahmer at the time was working for Larry at Sunshine.

She described Dahmer as an alcoholic living on the beach. Did Larry remember him?

Larry’s voice then began to quaver and his demeanor changed, she told me. Although he didn’t seem scared, “Larry clearly remembered Dahmer.” She hadn’t posed the inquiry as a question. “I told him, not asked him, that Dahmer was at Sunshine, looking for a confirmation.”

No, he said, but that was a long time ago. He’d had a lot of employees who fit that description.

Then he asked a question that struck her as odd:

“Is he dead?”

At that moment, Darlene told me, she got nausea.

He remembered the blue van – “that old van, with the carpet falling out, one seat in front.” He couldn’t remember the make and model either, he said, but it had been stolen from him, and he’d personally reported the theft to county police – referring to what was then called Metro-Dade Police. It was returned with its ignition torn out. Unable to use it, he sold it.

I’d given Darlene a list of questions to cover. Larry solved the Ken Houleb problem – his name was Ken Haupert, and two of them, father and son with the same name, both had worked for him. The father, about 20 years older than Larry, had worked at the main store, then Larry had him run Sunshine Sub. He’d divorced his wife and married an English girl who worked there – Maria, then later he said Susie. Then the two left town together.

Dahmer had described his boss’s age similarly, and said there was a younger woman who worked there, who was English:

Ken might have hired Dahmer, Larry said.

Houleb instead of Haupert – was that Dahmer forgetting? Or inventing a deniably close name that Hoffman wouldn’t be able to track ten years later, given no other clues?

After Darlene had left Sunshine, Larry installed a gas line and oven for hot subs and pizza. He said the store had made deliveries.

Now Darlene remembered: Ken Haupert had been a vice president for franchising at Nathan’s, the Coney Island hot dog chain. I remembered its store in Sunny Isles when I was first here in 1978. But he’d quit or lost his job and went to work for Larry – a big step down, she said.

After the phone call ended, Darlene was dissatisfied. “I’ve talked to Larry a million times. He remembers. He’s never not remembered – until now. All of the sudden, names changing, memory diminishing.”

Larry offered to look at the mugshot, but he emailed her back, saying he didn’t recognize it. On a second call, he was more reticent, she said. As she pushed for answers, he complained, “You’ve changed. You never used to ask a lot of questions.” That was true, she told me. Many things about Larry and his business she hadn’t wanted to know, or hadn’t tried to find out.

“Whatever he’s hiding from, I don’t think he’ll stick his neck out,” she told me. After that, Larry stopped taking her calls entirely. Denise and Robin tried him too, with no success.

I tried myself. I called his cell, but after telling him who I was, he quickly said he was busy and would call back. He never did. My later calls went unanswered.

Okay, super longshot, considering the degree of difficulty of each of these steps. I called a friend, Bob Foley, the retired head of the crime-scene unit at the Broward Sheriff’s Office, who had since returned home to Massachusetts to become the head of the criminal investigation bureau of the Barnstable County Sheriff, on Cape Cod. First I asked, if I could locate the van, could 20-year-old blood evidence be found and processed?

Yes, he said. On fabric, like a seat cover or carpet, blood seeps even into stitched seams. Imagine spilling ink, he said: “You can’t ever get it all cleaned.” On an exposed steel floor or wall, as in a van, blood would fill scratches and slight cracks. Swabs could remove samples even that small, and DNA could be detected. A thorough spray of luminol and then an infrared light shined over the area would find spatter or pooling patterns, which would indicate violence.

Foley was intrigued by my progress. He thought the Hollywood cops and the FBI were “stupid” not to have pursued Dahmer further. He made an offer: if I could find the van, and Hollywood Police didn’t care to check it, he would fly down and do it himself.

Next step: could I get the blue van’s vehicle identification number? I called a county vehicle registration office, which looked up vehicles registered to Larry. With the VIN, my plan was to enter it at Carfax to find later owners. First roadblock: Florida state vehicle records on computer then went back only 12 years, to 1990, and before that, information was spotty. Second obstacle: Larry’s file had a block on it, stopping public disclosure of his records. On the phone, the clerk had suddenly turned suspicious. He couldn’t tell, but I suggested it was because Larry had been a law enforcement officer. Later I got a cop friend to look it up for me, and that search did find vehicles under his name – but no vans.

One of the people I found who knew Larry and the vans suggested that Larry might have leased it from a Chevy dealer in nearby North Miami Beach, on the mainland. I called the dealership and spoke to the owner, whose name was on the dealership. He might have had it, but just months earlier he’d disposed of all his old records. He said it sounded like just an ordinary work van which at that point would have been at least twenty years old, making the chances of it still being on the road somewhere – slim.

So I moved on to trying to find Ken Haupert.

Dade and Broward phone books had no listings for Ken Haupert. In online county official records, in Broward I found two separate divorces under that name, in 1984 and 1985. At the Broward supervisor of elections, I checked the voter registration public database and found an address and date of birth for a Ken Haupert that suggested he was the son. In the online phone books I found a matching phone number.

After several attempts, I reached Ken Haupert on the first ring. Cautious, I told him I wasn’t sure I had the right person, I was looking for the Ken Haupert who’d worked at a sub shop in North Miami Beach 20 years ago. At first he sounded like he didn’t know what I was talking about.

“You sound too young,” I said. “The man I’m looking for is older.”

“I think you’re talking about my dad,” he said.

When I mentioned Dahmer, Haupert seemed genuinely surprised. He said he’d only worked at Sunshine and Beach Pizza because he was between jobs and to help out his father. He didn’t remember much because he hadn’t stayed long. Susie was the name of the English girl his dad was involved with, although he couldn’t recall her surname.

“When I found out the relationship, what was going on, I got pissed off and left.” He hadn’t spoken with his father since.

But he did help me find Ken Sr. Last he knew he’d opened a sub shop in Dewey, Oklahoma. He also gave me his father’s full name and date of birth.

Ken Jr. wanted to see Dahmer’s mugshot, which I emailed him.

Back to the Internet. Dewey was part of greater Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home to Phillips Petroleum, later ConocoPhillips. In the online phone books, Haupert wasn’t listed. Its chamber of commerce had no exclusively sub shops.

It was time to call my Delphic friend Jean again. Searching through a database of non-published phone numbers, she found Kenneth G. Haupert with a Dewey address. At first the phone just rang, then later, an electronic tone answered.

Ken Jr. called me back. As soon as he saw Dahmer’s mugshot he recognized him from the shop. So did his younger brother, coincidentally named Jeff. “When I told him, he was floored, Oh my god!”

They’d known him as Jeff, but may never have known his surname. “He wasn’t anybody you’d remember. He just worked there. He cleaned tables, helped with food preparation. There was nothing that stood out about him. He was like the average person who came into work to make his money.”

They’d never had any meaningful conversation with him. Jeff Haupert thought Dahmer might have been in the army.

Nor had they made the association in 1991 when Dahmer made the news. Checking other pictures on the Internet, they reported, “He looked different as he got older. It didn’t click in ’91, hey, I know that guy.”

In the shop, Dahmer had looked presentable, clean, clean-shaven, and not seedy-looking. Compared to the mugshot, he said, his hair, which was dirty blond, was flatter on top, combed more to the side, and he had no mustache, unlike in a later mugshot.

“But the face, definitely,” he said. He wore thick, out-of-fashion eyeglasses. “He looked like one of your friends, a guy you’d hang out with.” He remembered him wearing a T-shirt that read “Sunshine Sub.” He didn’t know who’d hired him. “Funny you’d work next to somebody like that. I guess that’s a claim to infamy.”

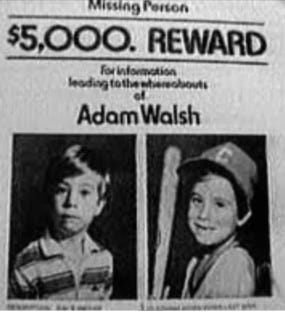

He also thought that the store had an Adam Walsh “Missing” poster.

He, as well, thought Larry had helped his father, who needed a break at the time, by setting him up at Sunshine and giving him money. “I don’t think it was totally my dad’s store. I think he was managing it.”

He didn’t know Larry was gay, though, or that he’d picked up drifters. He knew he didn’t have girlfriends, but he never saw him make advances toward men, or look at them in a homosexual way. Larry never made him feel uncomfortable. “You’d think of him as your brother.”

To track down Ken Sr., I called the records department in Washington County, Oklahoma, which encompassed Dewey and Bartlesville. They told me the Hauperts might have moved from the address Ken Jr. had given me. They suggested I call the electric company, which told me the same thing.

I knew where to call next: Dewey’s municipal water department. Getting the same answer, I asked the clerk if she knew of another city database, or property book, to scour for better information. While I kept her on the line, her boss, the city manager, peered over her shoulder and noticed Haupert’s name.

Wait, said the clerk, my boss knows him. He moved to Bartlesville with his business – Ian’s Sub Shop.

Could I speak to the city manager? She took the call. His new shop was in the lobby of a Bartlesville Best Western hotel. She politely offered to look up the phone number.

When I called it, the desk clerk said the Hauperts were away, it was their break time between lunch and dinner. Call back in an hour.

I did. The woman who answered had an English accent. I asked for her husband and she quickly put him on the line.

Ken Haupert Sr. was friendly, and of course, surprised. He said he only had a moment, they were preparing for their dinner business. After asking how I found him – I told him – he said Dahmer, in fact, had worked for him for a few months.

It was a Friday afternoon, and he asked if I could call back Monday. When I did, he was ready to talk about Jeffrey Dahmer.

And as Jon Stewart would go, Bam!

He met Dahmer, he said, when he saw him rummaging through the dumpster behind Sunshine Sub. He was picking out leftover pizza, to eat. “I said, Why are you doing that? He said, I’m hungry and I have no job. I said, Come in, I’ll give you something to eat.

“I gave him food, then a couple days later, he was back at the trash cans. I asked, I needed a busboy.

“Who knows who you meet in life?”

Haupert said he assigned Dahmer to general cleanup, including bussing tables and mopping floors. He worked Monday to Friday starting between 10-11 and ending between 4-5. He paid him minimum wage, plus meals.

Dahmer’s first two or three weeks on the job were okay, but then he became erratic. “All of the sudden he came in filthy dirty – like he was drinking all night, drunk and dirty, unable to work. I’d send him home, and the next day he’d be okay.”

But it became a frustrating pattern, starting again a week or so later. Once, he recalled, Dahmer came to work stinking, his eyeglasses broken. “He explained, I was running and fell down and broke my glasses.” Losing patience, Haupert told him, “Get out of here.”

Dahmer hadn’t wanted Haupert to know much about him. When he began asking why he was here, Jeff said he’d been kicked out of the army. Until I told him, Haupert didn’t know that it was for alcohol abuse. No, he’d never seen him wear army clothing.

Dahmer had seemed “hateful” toward his parents, whom he said were divorced. Did his father know where he was? No, Jeff admitted.

“I said, why don’t you speak to your parents?” So one day at the store, Haupert called and spoke to Lionel Dahmer, in Ohio, then handed Jeffrey the phone. That likely explained how Lionel Dahmer knew that Jeff had worked at a sub shop in Miami Beach.

Finally, after three months, “I got fed up and fired him.” That was their last contact.

“He was a bum,” he said. “He turned into a bum.”

Could one of those weekday mornings in 1981 when Dahmer came in drunk, and Haupert sent him away, have been Monday, July 27? Haupert said he’d kept employee records, but hadn’t saved them from twenty years earlier.

I said, Dahmer had told the police he’d gotten unemployment compensation while he was working at Sunshine. Haupert said he didn’t know that and asked how. I said, Dahmer admitted lying to the authorities. “He was quite good at lying,” Haupert commented.

Dahmer was also extremely quiet. “I’d ask, did you clean the bathroom good? He’d answer, but he was not one for conversation.” Nor did Dahmer seem to relate to employees. Haupert took his staff to a corner bar for occasions like birthdays, and “once in a while he’d join us.” And then, “he listened but never talked.”

When I asked about store vehicles, Haupert recalled a blue van. It was a Dodge, he said, and it was brand-new. Larry had bought it for both Sunshine and Beach Pizza. They used it for getting supplies and making deliveries.

Did Dahmer drive it? Given Dahmer’s obvious alcohol problems, “I wouldn’t let him drive anything. We had regular delivery people.”

Haupert said he kept the keys in his pocket. But, as he described, Dahmer would have been familiar with the blue van – and undoubtedly knew it was shared with Beach Pizza.

Haupert said Dahmer had no car of his own. “He had no money for a car.”

Did Dahmer know Larry? No, he didn’t think so. Nor did he see any indication that Dahmer was homosexual.

I emailed him the August 1982 mugshot, and he emailed back, “Yes, that’s Jeffrey, but he had no mustache.”

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

The two guys who said they saw Jeffrey Dahmer at the Hollywood Mall – and who the cops did their best to disregard.

You’re this far, you’ll want to keep reading, there’s so much more about this story you had no idea about. And now we’re in Part 4, the Dahmer section. FOLLOW, or SUBSCRIBE for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. But if you’re the type who pays for subscriptions on Substack, maybe you might consider me too? (I wouldn’t mind in the least.)

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular

When I mentioned Dahmer, Haupert seemed genuinely surprised. He said he’d only worked at Sunshine and Beach Pizza because he was between jobs and to help out his father. He didn’t remember much because he hadn’t stayed long. Susie was the name of the English girl his dad was involved with, although he couldn’t recall her surname.

“When I found out the relationship, what was going on, I got pissed off and left.” He hadn’t spoken with his father since.

But he did help me find Ken Sr. Last he knew he’d opened a sub shop in Dewey, Oklahoma. He also gave me his father’s full name and date of birth.

Ken Jr. wanted to see Dahmer’s mugshot, which I emailed him.

Back to the Internet. Dewey was part of greater Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home to Phillips Petroleum, later ConocoPhillips. In the online phone books, Haupert wasn’t listed. Its chamber of commerce had no exclusively sub shops.

It was time to call my Delphic friend Jean again. Searching through a database of non-published phone numbers, she found Kenneth G. Haupert with a Dewey address. At first the phone just rang, then later, an electronic tone answered.

Ken Jr. called me back. As soon as he saw Dahmer’s mugshot he recognized him from the shop. So did his younger brother, coincidentally named Jeff. “When I told him, he was floored, Oh my god!”

They’d known him as Jeff, but may never have known his surname. “He wasn’t anybody you’d remember. He just worked there. He cleaned tables, helped with food preparation. There was nothing that stood out about him. He was like the average person who came into work to make his money.”

They’d never had any meaningful conversation with him. Jeff Haupert thought Dahmer might have been in the army.

Nor had they made the association in 1991 when Dahmer made the news. Checking other pictures on the Internet, they reported, “He looked different as he got older. It didn’t click in ’91, hey, I know that guy.”

In the shop, Dahmer had looked presentable, clean, clean-shaven, and not seedy-looking. Compared to the mugshot, he said, his hair, which was dirty blonde, was flatter on top, combed more to the side, and he had no mustache, unlike in a later mugshot.

“But the face, definitely,” he said. He wore thick, out-of-fashion eyeglasses. “He looked like one of your friends, a guy you’d hang out with.” He remembered him wearing a T-shirt that read “Sunshine Sub.” He didn’t know who’d hired him. “Funny you’d work next to somebody like that. I guess that’s a claim to infamy.”

He also thought that the store had an Adam Walsh “Missing” poster.

He, as well, thought Larry had helped his father, who needed a break at the time, by setting him up at Sunshine and giving him money. “I don’t think it was totally my dad’s store. I think he was managing it.”

He didn’t know Larry was gay, though, or that he’d picked up drifters. He knew he didn’t have girlfriends, but he never saw him make advances toward men, or look at them in a homosexual way. Larry never made him feel uncomfortable. “You’d think of him as your brother.”

To track down Ken Sr., I called the records department in Washington County, Oklahoma, which encompassed Dewey and Bartlesville. They told me the Hauperts might have moved from the address Ken Jr. had given me. They suggested I call the electric company, which told me the same thing.

I knew where to call next: Dewey’s municipal water department. Getting the same answer, I asked the clerk if she knew of another city database, or property book, to scour for better information. While I kept her on the line, her boss, the city manager, peered over her shoulder and noticed Haupert’s name.

Wait, said the clerk, my boss knows him. He moved to Bartlesville with his business – Ian’s Sub Shop.

Could I speak to the city manager? She took the call. His new shop was in the lobby of a Bartlesville Best Western hotel. She politely offered to look up the phone number.

When I called it, the desk clerk said the Hauperts were away, it was their break time between lunch and dinner. Call back in an hour.

I did. The woman who answered had an English accent. I asked for her husband and she quickly put him on the line.

Ken Haupert Sr. was friendly, and of course, surprised. He said he only had a moment, they were preparing for their dinner business. After asking how I found him – I told him – he said Dahmer, in fact, had worked for him for a few months.

It was a Friday afternoon, and he asked if I could call back Monday. When I did, he was ready to talk about Jeffrey Dahmer.

And as Jon Stewart would go, Bam!

He met Dahmer, he said, when he saw him rummaging through the dumpster behind Sunshine Sub. He was picking out leftover pizza, to eat. “I said, Why are you doing that? He said, I’m hungry and I have no job. I said, Come in, I’ll give you something to eat.

“I gave him food, then a couple days later, he was back at the trash cans. I asked, I needed a busboy.

“Who knows who you meet in life?”

Haupert said he assigned Dahmer to general cleanup, including bussing tables and mopping floors. He worked Monday to Friday starting between 10-11 and ending between 4-5. He paid him minimum wage, plus meals.

Dahmer’s first two or three weeks on the job were okay, but then he became erratic. “All of the sudden he came in filthy dirty – like he was drinking all night, drunk and dirty, unable to work. I’d send him home, and the next day he’d be okay.”

But it became a frustrating pattern, starting again a week or so later. Once, he recalled, Dahmer came to work stinking, his eyeglasses broken. “He explained, I was running and fell down and broke my glasses.” Losing patience, Haupert told him, “Get out of here.”

Dahmer hadn’t wanted Haupert to know much about him. When he began asking why he was here, Jeff said he’d been kicked out of the army. Until I told him, Haupert didn’t know that it was for alcohol abuse. No, he’d never seen him wear army clothing.

Dahmer had seemed “hateful” toward his parents, whom he said were divorced. Did his father know where he was? No, Jeff admitted.

“I said, why don’t you speak to your parents?” So one day at the store, Haupert called and spoke to Lionel Dahmer, in Ohio, then handed Jeffrey the phone. That likely explained how Lionel Dahmer knew that Jeff had worked at a sub shop in Miami Beach.

Had Haupert not done that (and then Lionel told that to police in Milwaukee), it seems unlikely to me that we would have ever known that Jeff had been in Miami Beach.

Finally, after three months, “I got fed up and fired him.” That was their last contact.

“He was a bum,” he said. “He turned into a bum.”

Could one of those weekday mornings in 1981 when Dahmer came in drunk, and Haupert sent him away, have been Monday, July 27? Haupert said he’d kept employee records, but hadn’t saved them from twenty years earlier.

I said, Dahmer had told the police he’d gotten unemployment compensation while he was working at Sunshine. Haupert said he didn’t know that and asked how. I said, Dahmer admitted lying to the authorities. “He was quite good at lying,” Haupert commented.

Dahmer was also extremely quiet. “I’d ask, did you clean the bathroom good? He’d answer, but he was not one for conversation.” Nor did Dahmer seem to relate to employees. Haupert took his staff to a corner bar for occasions like birthdays, and “once in a while he’d join us.” And then, “he listened but never talked.”

When I asked about store vehicles, Haupert recalled a blue van. It was a Dodge, he said, and it was brand-new. Larry had bought it for both Sunshine and Beach Pizza. They used it for getting supplies and making deliveries.

Did Dahmer drive it? Given Dahmer’s obvious alcohol problems, “I wouldn’t let him drive anything. We had regular delivery people.”

Haupert said he kept the keys in his pocket. But, as he described, Dahmer would have been familiar with the blue van – and undoubtedly knew it was shared with Beach Pizza.

Haupert said Dahmer had no car of his own. “He had no money for a car.”

Did Dahmer know Larry? No, he didn’t think so. Nor did he see any indication that Dahmer was homosexual.

I emailed him the August 1982 mugshot, and he emailed back, “Yes, that’s Jeffrey, but he had no mustache.”

Next on Adam Walsh: America’s Missing Child:

You’re really far now, you’ll want to keep reading, there’s so much more about this story you had no idea about. And now we’re getting into the Jeffrey Dahmer section. FOLLOW, or SUBSCRIBE now for FREE and you won’t miss any new episode. But if you’re the type who pays for subscriptions on Substack, maybe you might consider me too? (I wouldn’t mind in the least.)

#true crime, #truecrime, #cold case, #katie, #terry, @meidas, @paul, @joy, @robert, @gavin, @sharyl, @aaron, @bulwark, @lincoln, @popular, #investigative